by Mik Andersen, Corona2Inspect

published in Spanish December 16, 2021

rough translation via translation software

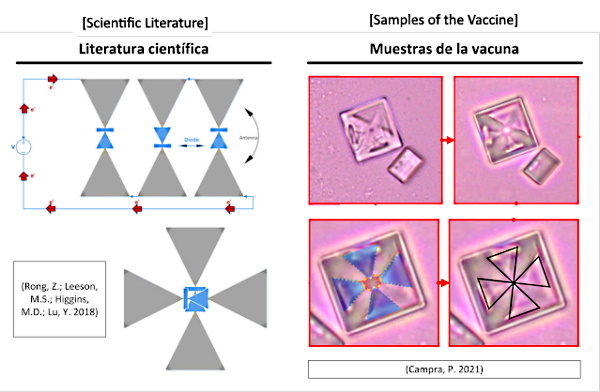

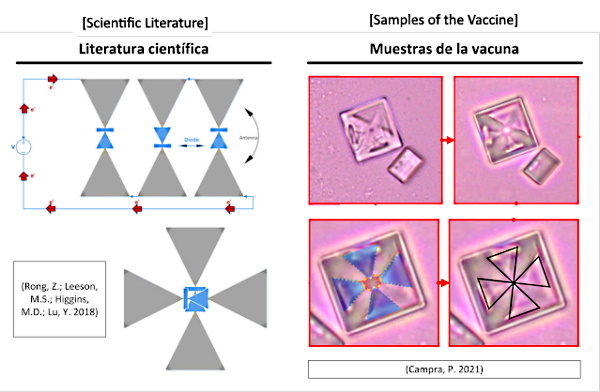

Research on nanocommunication networks for nanodevices inoculated in the human body continues to accumulate evidence. On this occasion, the article by the researchers (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) is presented entitled “Nanoredes centered in the body driven by nano-Rectenna in the terahertz band = Nano- rectenna powered body-centric nano-networks in the terahertz band” which confirms the theory that Corona2Inspect had been studying through the observation of the images of the samples of the c0r0n @ v | rus vaccines obtained by the doctor (Campra, P. 2021). Nano-arrays centered on the human body require the use of nano-antennas that operate in the terahertz band, these being the same type as those found in the vaccine samples ..

In the literature, these plasmonic nano-antennas are also called bowtie antennas or “bowties antenna” and in the article in question they are called “nano-rectennas”. The explicit mention of the type of antenna and the technology of intra-body nano-networks, would confirm that vaccines are, among other things, vectors for the installation of nanotechnology, or nanodevices in the human body. However, beyond the pure coincidence, the authors make explicit the use of graphene and carbon nanotubes, as necessary elements for this network model, elements that were also identified in the images taken by Dr. Campra and that coincide with the presence of graphene in its technical report with spectroscopy. Micro-Raman.

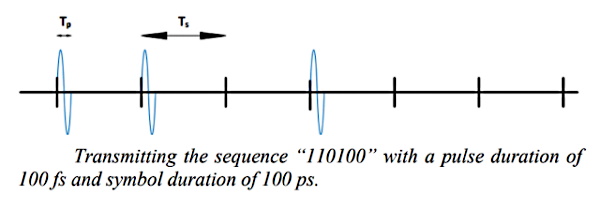

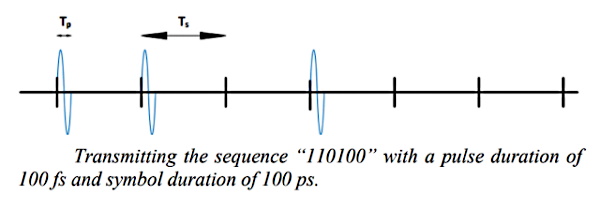

To what has already been described, the article adds that the method of communication and data transmission in nano-networks is carried out through TS-OOK signals (sequences of pulses that transmit binary codes), which matches with studies and protocols of nanocommunications and would endorse all the research carried out by Corona2Inspect so far on this matter.

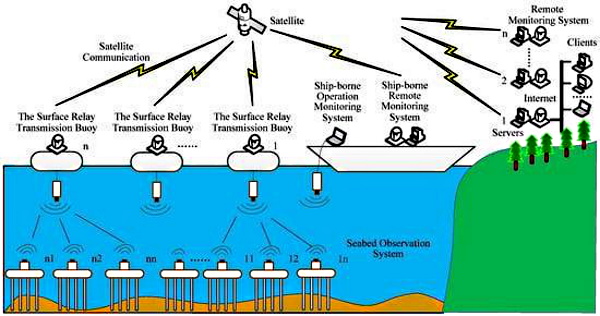

If what has been explained is not enough to confirm the theory of intracorporeal communication nano-networks, the article by (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) makes explicit the use of nano-sensors that are linked by means of electromagnetic signals, by means of the aforementioned nano-rectennas or bow tie nano-antennas, which necessarily evidences the presence of nano-routers that serve to manage the intra-body and out-of-body data link, with gateways (gateway) such as mobile phone. Given the importance of the content of the article, it will be dissected in detail.

Article analysis

The research object of the work of (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) is the comparative analysis of the energy harvesting capacities of nano-rectennas, aimed at their implementation in networks wireless nanodevices and intra-body nanotechnology. This is reflected in the introduction of the article as follows “in the field of health applications, the objective is to develop a network of therapeutic nanodevices that is capable of working in the human body or within it to support the monitoring of the immune system, health monitoring, drug delivery systems and biohybrid implants “. This leaves no doubt that nano-antennas, here called nano-rectennas, necessarily imply the presence of a network of nanodevices or nanotechnology aimed at controlling the biological variables and factors of people.

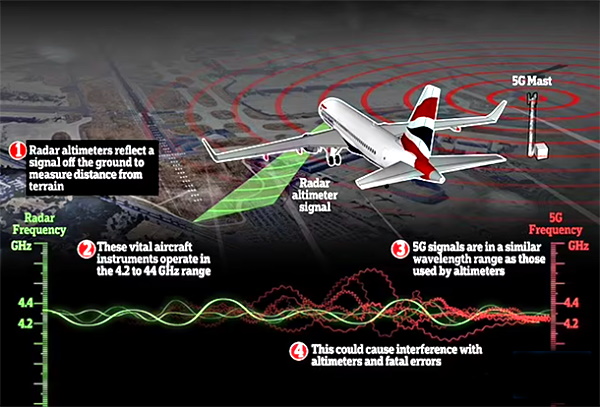

Furthermore, (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) state that “There are two main approaches to nanoscale wireless communications, namely, molecular and electromagnetic (EM) communications (Akyildiz, IF; Jornet, JM 2010). The latter commonly operates in the terahertz (THz) band (0.1-10 THz) and is a promising technique to support data exchange in nanosensor networks for healthcare applications or body-centered nano-networks. For the expected size of nanosensors, the frequency radiated by their antennas would normally be in the optical range, resulting in a very large channel attenuation that could make nanoscale wireless communication unfeasible. To overcome this limitation, graphene-based antennas have been developed, which are able to resonate in the THz band with sizes of a few ??, at a frequency up to two orders of magnitude lower than a metallic antenna of the same dimensions“.

This explanation corroborates the two types of intra-body communication , the molecular type used for monitoring and neuromodulation of neuronal tissue and the central nervous system ( Akyildiz, IF; Jornet, JM; Pierobon, M. 2011 | Malak, D.; Akan, OB 2012 | Rikhtegar, N.; Keshtgary, M. 2013 | Balasubramaniam, S.; Boyle, NT; Della-Chiesa, A.; Walsh, F.; Mardinoglu, A.; Botvich, D.; Prina-Mello , A. 2011) and electromagnetic, conceived for the control of biological variables and factors in the rest of the body, by means of nano-nodes (also known as nano-devices, nano-biosensors, etc.).

It also corroborates the operating band in which the intra-body nano-network is operating, in a range of 0.1-10 THz, confirmed in this blog according to (Abbasi, QH; Nasir, AA; Yang, K.; Qaraqe, KA ; Alomainy, A. 2017 | Zhang, R.; Yang, K.; Abbasi, QH; Qaraqe, KA; Alomainy, A. 2017 | Yang, K.; Bi, D.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, R. ; Rahman, MMU; Ali, NA; Alomainy, A. 2020). It also addresses the fact that the scale of the nano-devices, nano-sensors of the network forces to “resonate the THz band” by means of special antennas of a few microns (??), but with the ability to retransmit signals and in turn of harvesting energy to run the grid. These special properties are achieved through the plasmonic effect given by the nanoantennas scale, which confers special physical and quantum properties to these objects, as explained in (Jornet, JM; Akyildiz, IF 2013 | Nafari, M.; Jornet, JM 2015 | Guo , H.; Johari, P.; Jornet, JM; Sun, Z. 2015 ).

In the introductory dissertation, (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) mention a substantial aspect “the exchange of information between implantable [injectable] nanosensors is the most significant, since it allows control and monitoring the release or flux of molecular, biochemical compounds, and other important functions within the human body.” The relevance of this statement is crucial since it assumes that nanodevices have to be installed, injected or implanted in the human body, but also that it is necessary to receive their signals and data generated to carry out the corresponding monitoring, even at the level of molecular flow and biochemical compounds, such as neurotransmitters produced by neuronal tissue or the nervous system ( Abd-El-atty, SM; Lizos, KA; Gharsseldien, ZM; Tolba, A.; Makhadmeh, ZA 2018).

This explains the need to introduce graphene, carbon nanotubes and derivatives to capture these signals and bio-electrical markers to capture the information, but also a wireless nano-network, which allows transmitting this data outside the human body. Therefore, it must be understood that the nano-antennas or nano-rectennas in charge of repeating the signals could not only do it from the inside out, being able to carry out the reverse process, altering the neuronal synapse, for example.

Likewise, (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) state that a relevant problem in intra-body nano-networks is the availability of energy (Bouchedjera, IA; Aliouat, Z.; Louail , L. 2020 | Fahim, H.; Javaid, S.; Li, W.; Mabrouk, IB; Al-Hasan, M.; Rasheed, MBB 2020 ), for which efficient routing protocols and processes have been developed ( Sivapriya, S.; Sridharan, D. 2017 | Piro, G.; Boggia, G.; Grieco, LA 2015 ) that make the operation of the nano-network plausible. For the purposes of nano-antennas or nano-rectennas, Rong and his team state the following: “One of the biggest challenges in body-centered nanogrids is caused by the very limited energy storage of a nano battery … Since electromagnetic waves carry not only information but also energy, rectenins can operate at THz and frequencies. microwave, allowing them to work overnight. Since electromagnetic waves carry not only information, but also energy ( Varshney, LR 2008 ), nano-rectennas can share the same signal that is used to carry information within nano-networks. As a result, simultaneous wireless information and power transfer (SWIPT) becomes a critical technique for powering nanogrids and is a promising solution to power bottlenecks … A major advantage of the The technique is that the proposed nano-rectennas are capable of converting an EM signal into a direct current without any external power supply of the system. In addition, achievable energy conversion achieves approximately 85% efficiency.“.

These statements are fundamental to confirm that EM electromagnetic waves, or what is the same microwave, serve to transport energy and data simultaneously, being able to do so in the THz band compatible with the intra-body wireless network.

This confirms what has been explained in the entry on nanocommunication networks for nanotechnology in the human body, published on this blog. This ambivalent phenomenon of transporting energy and data is known by the acronym SWIPT, which allows us to infer that nano-antennas or nano-rectennas have this property. In fact, the authors affirm its ability to convert an EM signal into direct current without external power, with a very high efficiency, which would explain why enough energy was generated and probably stored to make the intra-body network work. In fact, according to (Zainud-Deen, SH; Malhat, HA; El-Araby, HA 2017) nanoantennas with a geometric diode such as bow tie or other polygonal type, based on graphene, not only collect energy from electromagnetic waves EM ( microwave), they can also do it with the infrared spectrum (El-Araby, HA; Malhat, HA; Zainud-Deen, SH 2017 | 2018), which guarantees a constant flow of energy.

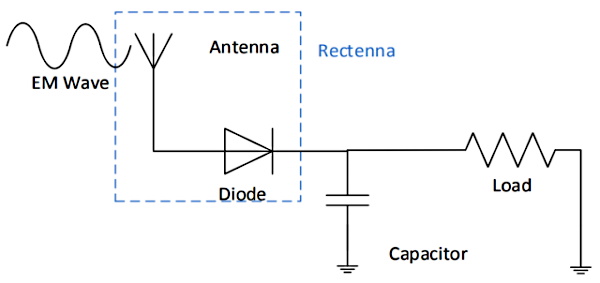

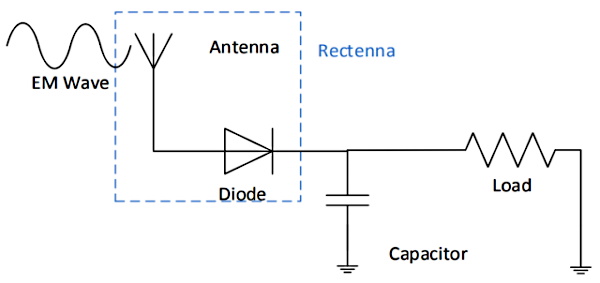

On the other hand, (Rong, Z .; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) define the concept of rectenna as “a combination of an antenna and a rectifier device, generally a diode, with the purpose of collecting energy in and to the nanowires, so that the EM waves are received by a nano antenna and then coupled to a rectifier … this makes it possible for them to be used to harvest energy from THz and higher frequencies. How nano-sized antennas operate In the THz band, their associated rectifier diodes need a fast response so that they can react properly to the incoming signal and deliver a DC (Direct Current) signal … The rectifier can collect energy from the THz signal or from residual energy in the environment“.

However, it is known that rectennas are also capable of transmitting and collecting energy and data in the GHz band as explained in the work of ( Suh, YH; Chang, K. 2002 | Abdel-Rahman, MR; Gonzalez, FJ; Boreman, GD 2004 ) .In this regard, the work of ( Khan, AA; Jayaswal, G .; Gahaffar, FA; Shamim, A. 2017, should also be highlighted .) in which it is shown that nano-rectennas are capable of collecting energy from environmental radio frequency (RF) for which they use tunneling diodes, which hardly consume energy during the process of conversion to direct current. These tunneling diodes also known as MIM (metal-insulator-metal) diodes can provide zero bias rectification, allowing it to operate in a frequency range between 2-10GHz, allowing it to adapt to input impedance.

In fact, Khan and his team state that “Although the real advantage of MIM diodes is the high frequencies (THz range), their zero-bias rectification ability can also be beneficial for collecting and wireless feeding at RF frequencies. .. Characterization of DC (Direct Current) indicated that the MIM diode could provide a zero bias responsiveness of 0.25V -1 with a decent dynamic resistance of 1200 Ω (Ohms). The metal-insulator-diode-metal RF (Radio Frequency) characterization was performed using two methods: 1) S parameter measurements (Diode tunnel barrier thickness) from 500MHz to 10 GHz, and 2) RF rectification to DC with zero polarization. The presented input impedance results may be useful for integrating MIM diodes with antennas for harvesting applications. The second part of the RF characterization verified the rectification of RF to DC zero bias.”

In other words, the researchers confirm that nano-rectennas can operate in lower frequency ranges and even by radio frequency, which explains that it makes them the ideal method for powering wireless nano-networks and their connection applications. to the IoNT (Internet of NanoThings).

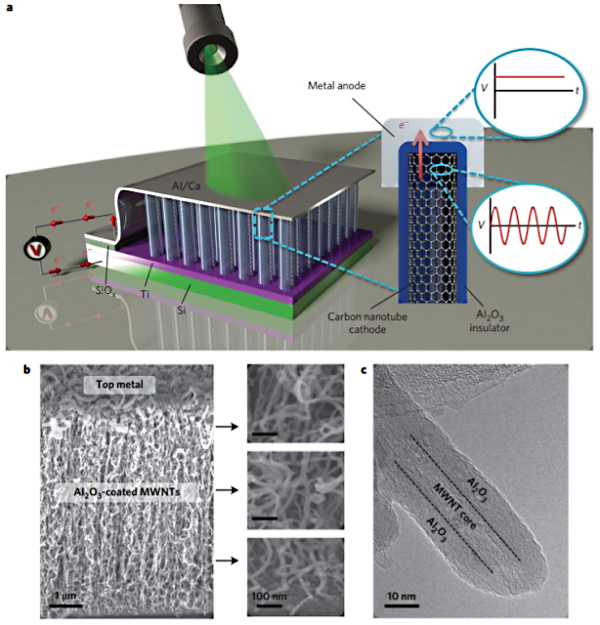

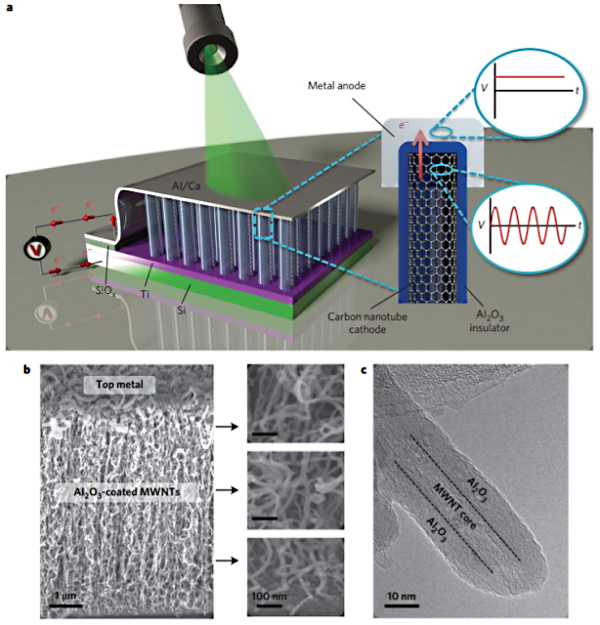

Returning to the analysis of (Rong, Z.; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018), his work addresses the comparison of two types of rectenins oriented to intra-body nano-networks. One of them is nano-rectena based on carbon nanotubes, which matches with the identifications observed in the vaccine samples . In this sense, Rong and his team cite the work of (Sharma, A.; Singh, V.; Bougher, TL; Cola, BA 2015) who proposed the rectennas of CNT (Carbon Nanotubes) “which consisted of millions of nanotubes that functioned as nano antennas, with their tips made of Insulator-Metal (IM) to behave like diodes. The CNT rectennas showed great potential for body-centered nanodevice applications and wireless EM energy harvesting.”

This could confirm that the observed carbon nanotubes and plasmonic nanoantennas are intended, among others, to deliver energy. To the nano-network installed with the different inoculations of the vaccine, an aspect that would explain the need for several doses to complete the basic supply of energy for its perpetual operational maintenance. Abundant in the carbon nanotube rectennas, it is also stated that “When CNTs absorb EM radiation, a direct current will be generated after rectification across the tip area. This converted current is used to charge a capacitor. The process of conversion to DC (Direct Current) is carried out using the THz signal within the system and environmental free EM, so the power source of such a nano-rectenna generator does not need another specific external power source.” Which suggests that no other components are required to function.

In addition to CNT nano-rectennas, (Rong, Z .; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. 2018) compare them with their main proposal, bow tie nano-rectennas “dipole nano-rectennas have been proposed bow tie, with two triangular sections. The thickness of the antenna is 100 nm, and nano diodes, made of graphene located in the middle of the hole area of the bow tie antenna, producing the action of the rectena. Additionally, can connect to form a nano-rectilinear array or array. The bowtie dipole antenna receives EM radiation and converts the signal into AC (alternating current) flux to the nano diode. The diode then rectifies the AC (alternating current) into current continue DC “.

This would confirm the type of Plasmon nano-antennas observed in the vaccine samples , as well as the graphene material used as a link between their triangular sections, which matches with the presence of graphene detected by Campra in the vaccines . Another relevant detail is also provided, nano-rectennas can operate in a matrix or array, which means that thousands of them can operate, as stated by Rong and his team “As the output power of a single rectenine is 0.11 nW (approximately), if we use an array of these lines, the power and size required by the nano-network can be satisfied … More elements connected in series can increase the production of current and power “.

This is demonstrated in the work of ( Aldrigo, M .; Dragoman, M. 2014 ) entitled “Nano-rectennas based on graphene in the far infrared frequency band where it is explained that nano-rectennas are capable of collecting human heat in the infrared frequency band, and that the The proposed model is encouraging “both in terms of the rectified current of a single nano-receptor, as well as the power rectified by a macro-system that combines thousands of nano-cells“. Which leaves no doubt that nano-rectennas are not an isolated component, in fact they are more common and numerous than might be thought a priori. Perhaps one dose of the vaccine involves thousands or perhaps millions of nano-rectennas, depending on its scale.

Rong’s article continues to provide very relevant keys, this time in relation to the CNT rectennes, indicating that “the output voltage generated by the CNT rectena is of the order of tens of millivolts … the channel access scheme for the communications will be based on femtosecond pulses to the nanowire … the digits 1 (of the binary code) are transmitted using pulses of 100??, this is a long pulse, while the digits 0 are transmitted as silence … as the time The separation between adjacent bits is 1000 times the pulse duration (Ts = 100ps), the average power will return to the nW level. Therefore, the output power of the CNT rectenna is able to satisfy the power requirements of the system (from the nanoret)“.

This statement confirms what was already investigated in Corona2Inspect, nanogrids operate with TS-OOK signals for the transfer of data packets (see nanocommunication networks for nanotechnology in the human body , CORONA system for nanogrids , nanorouters , nanogrids software electromagnetic ) due to their simplicity and reduced energy consumption. Furthermore, it confirms that carbon nanotubes can operate in the transmission of signals and data, as well as the collection of energy, as was suggested in the entry on nano octopuses and carbon nanotubes of this blog .

According to Rong’s calculations, “For a rectenna CNT device, the maximum reported output voltage is 68 mV and for a 25-element rectenna bowtie array it is 170 mV. Therefore, according to (9), the rectena matrix bowtie (bow tie) delivers more charge than rectena CNT … when these two rectena devices are used to charge the same ultra-nano capacitor (9nF), it is evident that rectena CNT takes longer (more than 6 minutes) due to its very high junction resistance. Whereas for the rectena bow tie, the resistance is comparatively very small, so it only takes about 6 ms to supply more power to the capacitor“. This explanation is very important when comparing the two types of rectenna for intra-body nano-networks.

Arrayed bow tie nano-rectennas present better performance than those based on carbon nanotubes, taking a nano-capacitor to charge in only 6 milliseconds. This would explain the presence of these components in the vaccine samples, at micro and nano-scale. In addition, the allusion to the ultra-nanocapacitors used to perform the load test is relevant. Capacitors are passive electrical devices capable of of storing energy by maintaining an electric field.

This could lead to the question: Where is energy stored in intra-body nano-grids?

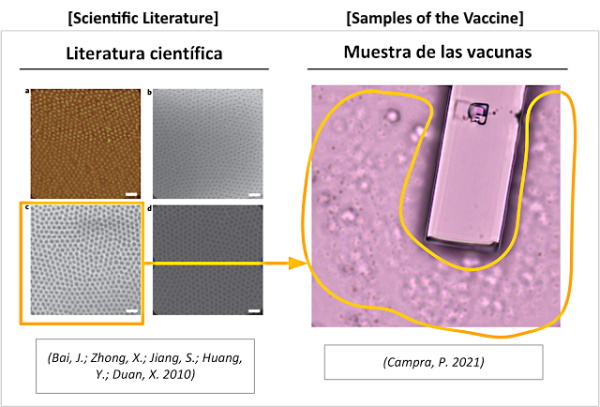

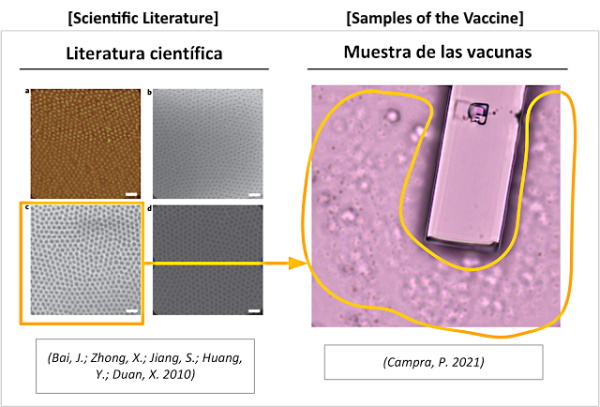

The answer is very simple, in an abundant and recognized material in vaccines, this is graphene itself. act as capacitors, as shown in the work of ( Bai, J .; Zhong, X .; Jiang, S .; Huang, Y .; Duan, X. 2010 ), because “the graphene sheets nanoribbons with widths less than 10 nm can open a band gap large enough for operation as transistor at room temperature“. This is de facto what allows the generation of a magnetic field, as a result of the electrical charge transmitted by the nano-rectennas.

This would explain the phenomenon of magnetic arms (among other parts of the body) after inoculation of the vaccines. In fact, if you look at figure 5, a nano-mesh (made of graphene) similar to that found in the scientific literature can be seen blurred, which could act as a condenser. In many cases, these shapes were found around polygonal, quadrangular objects. and nano-antennas, which seems to make sense to provide an energy carryover for nano-grids.

Finally, among the conclusions, Rong and his team highlight the following “Along with the continuous advancement of the SWIPT technique ( simultaneous wireless information and power transfer) , the pioneering CNT matrix receiver and the nano-matrix bowtie (bowtie) open the door for wireless nano-sensor powering. Since a nano-rectenna is capable of powering nanosensors without any external source and its broadband property allows rectenna to be a very efficient and promising way to power implanted nanodevices and in the human body. CNT’s rectenna array can successfully deliver the required human body-centric wireless nano-network power, estimated to be around 27.5 nW. Also, the bow tie rectifier array is much smaller in size, but provides similar power … Although nano-rectenins cannot provide such a high voltage compared to a piezoelectric nanogenerator, an array of nano-rectennas bowtie (bowtie) is much more efficient producing in addition DC (Direct Current) directly from the THz signal within the system (the human body) and the environmental EM signal without any other external power source of the system“.

This seems to make it clear that this type of nano-antennas are the appropriate ones, if what is desired is to install intra-corporal nano-networks of nanodevices and nanosensors. Therefore, a very sharp deduction is not necessary to realize that the The presence of plasmonic nano-antennas in the vaccine samples, whether in the shape of a bow tie or cube, or a prism, as has been observed, are clear evidence of the presence of undeclared nanotechnology.

Bibliography

- Abbasi, QH; Nasir, AA; Yang, K .; Qaraqe, KA; Alomainy, A. (2017). Cooperative in-vivo nano-network communication at terahertz frequencies. IEEE Access, 5, pp. 8642-8647. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2677498

- Abd-El-atty, SM; Lizos, KA; Gharsseldien, ZM; Tolba, A .; Makhadmeh, ZA (2018). Engineering molecular communications integrated with carbon nanotubes in neural sensor nanonetworks. IET Nanobiotechnology, 12 (2), 201-210. https://ietresearch.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1049/iet-nbt.2016.0150

- Abdel-Rahman, MR; Gonzalez, FJ; Boreman, GD (2004). Antenna-coupled metal-oxide diodes for dual-band detection at 92.5 GHz and 28 THz = Antenna-coupled metal-oxide-metal diodes for dual-band detection at 92.5 GHz and 28 THz. Electronics Letters, 40 (2), pp. 116-118. https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1049/el:20040105

- Akyildiz, IF; Jornet, JM (2010). Electromagnetic wireless nanosensor networks = Electromagnetic wireless nanosensor networks. Nano Communication Networks, 1 (1), pp. 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nancom.2010.04.001

- Akyildiz, IF; Jornet, JM; Pierobon, M. (2011). Nanonetworks: a new frontier in communications = Nanonetworks: A new frontier in communications. Communications of the ACM, 54 (11), pp. 84-89. https://doi.org/10.1145/2018396.2018417

- Aldrigo, M .; Dragoman, M. (2014). Graphene-based nano-rectenna in the far infrared frequency band = Graphene-based nano-rectenna in the far infrared frequency band. In: 2014 44th European Microwave Conference (pp. 1202-1205). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EuMC.2014.6986657 | https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1109/eumc.2014.6986657

- Bai, J .; Zhong, X .; Jiang, S .; Huang, Y .; Duan, X. (2010). Graphene nano-mesh = Graphene nanomesh. Nature nanotechnology, 5 (3), pp. 190-194. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2010.8 | https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1038/nnano.2010.8

- Balasubramaniam, S .; Boyle, NT; Della-Chiesa, A .; Walsh, F .; Mardinoglu, A .; Botvich, D .; Prina-Mello, A. (2011). Development of artificial neuronal networks for molecular communication. Nano Communication Networks, 2 (2-3), pp. 150-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nancom.2011.05.004

- Bouchedjera, IA; Aliouat, Z .; Louail, L. (2020). EECORONA: Energy Efficiency Coordinate and Routing System for Nanonetworks = EECORONA: Energy Efficiency Coordinate and Routing System for Nanonetworks. In: International Symposium on Modeling and Implementation of Complex Systems. Cham. pp. 18-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58861-8_2

- Campra, P. (2021). Detection of graphene in COVID19 vaccines by Micro-RAMAN spectroscopy. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355684360_Deteccion_de_grafeno_en_vacunas_COVID19_por_espectroscopia_Micro-RAMAN

- El-Araby, HA; Malhat, HA; Zainud-Deen, SH (2017). Performance of nanoantenna-coupled geometric diode with infrared radiation = Performance of nanoantenna-coupled geometric diode with infrared radiation. In: 2017 34th National Radio Science Conference (NRSC) (pp. 15-21). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/NRSC.2017.7893471 | https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1109/NRSC.2017.7893471

- El-Araby, HA; Malhat, HA; Zainud-Deen, SH (2018). Nanoantenna with geometric diode for energy harvesting. Wireless Personal Communications, 99 (2), pp. 941-952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-017-5159-2

- Fahim, H .; Javaid, S .; Li, W .; Mabrouk, IB; Al-Hasan, M .; Rasheed, MBB (2020). An efficient routing scheme for intrabody nanonetworks using artificial bee colony algorithm. IEEE Access, 8, pp. 98946-98957. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2997635

- Guo, H .; Johari, P .; Jornet, JM; Sun, Z. (2015). Intra-body optical channel modeling for in vivo wireless nanosensor networks = Intra-body optical channel modeling for in vivo wireless nanosensor networks. IEEE transactions on nanobioscience, 15 (1), pp. 41-52. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNB.2015.2508042

- Jornet, JM; Akyildiz, IF (2013). Graphene-based plasmonic nano-antenna for terahertz band communication in nanonetworks = Graphene-based plasmonic nano-antenna for terahertz band communication in nanonetworks. IEEE Journal on selected areas in communications, 31 (12), pp. 685-694. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2013.SUP2.1213001

- Jornet, JM; Akyildiz, IF (2014). Long femtosecond pulse-based modulation for terahertz band communication in nanonetworks = Femtosecond-long pulse-based modulation for terahertz band communication in nanonetworks. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 62 (5), pp. 1742-1754. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2014.033014.130403

- Khan, AA; Jayaswal, G .; Gahaffar, FA; Shamim, A. (2017). Metal-insulator-metal diodes with sub-nanometer surface roughness for energy-harvesting applications. Microelectronic Engineering, 181, pp. 34-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2017.07.003

- Malak, D .; Akan, OB (2012). Molecular communication nanonetworks inside human body. Nano Communication Networks, 3 (1), pp. 19-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nancom.2011.10.002

- Nafari, M .; Jornet, JM (2015). Metallic plasmonic nano-antenna for wireless optical communication in intra-body nanonetworks. In: Proceedings of the 10th EAI International Conference on Body Area Networks (pp. 287-293). https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.28-9-2015.2261410

- Piro, G .; Boggia, G .; Grieco, LA (2015). On the design of an energy-harvesting protocol stack for Body Area Nano-NETworks. Nano Communication Networks, 6 (2), pp. 74-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nancom.2014.10.001

- Reed, JC; Zhu, H .; Zhu, AY; Li, C .; Cubukcu, E. (2012). Graphene-enabled silver nanoantenna sensors = Graphene-enabled silver nanoantenna sensors. Nano letters, 12 (8), pp. 4090-4094. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl301555t

- Rikhtegar, N .; Keshtgary, M. (2013). A brief review on molecular and electromagnetic communications in nano-networks = A brief survey on molecular and electromagnetic communications in nano-networks. International Journal of Computer Applications, 79 (3). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.402.8701&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Rong, Z .; Leeson, MS; Higgins, MD; Lu, Y. (2018). Body-centered nano-networks powered by nano-Rectena in the terahertz band = Nano-rectenna powered body-centric nano-networks in the terahertz band. Healthcare technology letters, 5 (4), pp. 113-117. http://dx.doi.org/10.1049/htl.2017.0034 | https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322782473_Nano-Rectenna_Powered_Body-Centric_Nanonetworks_in_the_Terahertz_Band | https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1049/htl.2017.0034

- Sharma, A .; Singh, V .; Bougher, TL; Cola, BA (2015). Carbon nanotube optical rectenna = A carbon nanotube optical rectenna. Nature nanotechnology, 10 (12), pp. 1027-1032. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.220

- Sivapriya, S .; Sridharan, D. (2017). Energy Efficient MAC Protocol for Body Centric Nano-Networks (BANNET) = Energy Efficient MAC Protocol for Body Centric Nano-Networks. ADVANCED COMPUTING (ICoAC 2017), 422. https: //www.researchgate.net/profile/H-Mohana/publication/322790171 …

- Suh, YH; Chang, K. (2002). High-efficiency dual-frequency rectenna for 2.45 and 5.8 GHz wireless power transmission = A high-efficiency dual-frequency rectenna for 2.45-and 5.8-GHz wireless power transmission. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, 50 (7), pp. 1784-1789. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMTT.2002.800430 | https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1109/TMTT.2002.800430

- Varshney, LR (2008). Transporting information and energy simultaneously = Transporting information and energy simultaneously. In: 2008 IEEE international symposium on information theory (pp. 1612-1616). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ISIT.2008.4595260

- Yang, K .; Bi, D .; Deng, Y .; Zhang, R .; Rahman, MMU; Ali, NA; Alomainy, A. (2020). A comprehensive survey on hybrid communication in context of molecular communication and terahertz communication for body-centric nanonetworks. IEEE Transactions on Molecular, Biological and Multi-Scale Communications, 6 (2), pp. 107-133. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMBMC.2020.3017146

- Yang, K .; Pellegrini, A .; Munoz, MO; Brizzi, A .; Alomainy, A .; Hao, Y. (2015). Numerical analysis and characterization of THz propagation channel for body-centric nano-communications. IEEE Transactions on Terahertz Science and technology, 5 (3), pp. 419-426. https://doi.org/10.1109/TTHZ.2015.2419823

- Zainud-Deen, SH; Malhat, HA; El-Araby, HA (2017). Energy harvesting enhancement of nanoantenna coupled to geometrie diode using transmitarray. In: 2017 Japan-Africa Conference on Electronics, Communications and Computers (JAC-ECC) (pp. 152-155). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/JEC-ECC.2017.8305799 | https://sci-hub.mksa.top/10.1109/JEC-ECC.2017.8305799

- Zhang, R .; Yang, K .; Abbasi, QH; Qaraqe, KA; Alomainy, A. (2017). Analytical characterization of the terahertz in-vivo nano-network in the presence of interference based on TS-OOK communication scheme. IEEE Access, 5, pp. 10172-10181. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2713459

Connect with Corona2Inspect / Follow Corona2Inspect on Telegram

See related by Mik Andersen:

Graphene Oxide & Nano-Router Circuitry in Covid Vaccines: Uncovering the True Purpose of These Mandatory Toxic Injections