Indigenous Food Sovereignty Movements Are Taking Back Ancestral Land

From fishing rights off Nova Scotia, to grazing in Oklahoma and salmon habitats on the Klamath River, tribal groups are reclaiming their land and foodways.

by Melissa Montalvo, Civil Eats

March 31, 2021

Last November, escalating tensions between the Mi’kmaq First Nations people exercising their fishing rights and commercial fishermen in Nova Scotia resulted in an unexpected finale: A coalition of Mi’kmaq tribes bought 50 percent of Clearwater Seafoods, effectively giving them control of the billion-dollar company and one of the largest seafood businesses in North America.

The Mi’kmaq people, who compose 13 distinct nations in Nova Scotia alone, have relied on fishing for tens of thousands of years and were granted treaty rights to a “moderate livelihood” by Canada’s Supreme Court. Despite these protections, the Mi’kmaq faced resistance, hostility, and even violence from commercial fishermen when exercising their rights.

By becoming majority owners of Clearwater Seafoods, the Mi’kmaq gained full ownership of Clearwater’s offshore fishing licenses, which allow them to harvest lobster, scallop, crab, and clams in a large area extending from the Georges Bank to the Laurentian Channel off Cape Breton. Tribal leaders hope the purchase guarantees the food security and economic sustainability of Mi’kmaq communities for generations.

Indigenous food sovereignty activists across the world stood in solidarity with the Mi’kmaq and applauded their unexpected victory. The deal represents a growing trend: Indigenous people are regaining access to—and control of—their traditional foodways.

For centuries, Native Americans in the United States have endured countless atrocities, from massacre to forced removal from their ancestral lands by the federal government. This separation from the land is inextricably tied to the loss of traditional foodways, culture, and history.

Now, there is growing momentum behind the Indigenous food sovereignty movement. Over the past few decades, Native American tribes in the U.S. have been fighting for the return of ancestral lands for access to traditional foodways through organizing and advocacy work, coalition building, and legal procedure—and increasingly seeing success.

In recent years, the Wiyot Tribe in Northern California secured ownership of its ancestral lands and is working to restore its marine habitats; the nearby Yurok Tribe fought for the removal of dams along the Klamath River and has plans to reconnect with salmon, its traditional food source; and the Quapaw Nation in Oklahoma has cleaned up contaminated land to make way for agriculture and cattle businesses.

“A big part of [land reclamation] is for food sovereignty,” stressed Frankie Myers, vice chairman of the Yurok Tribe. “We depend on the land to eat, to gain protein. It’s what our bodies were accustomed to, it’s what we as a people are accustomed to—working out in the landscape. It’s where we feel home. It’s good for our mental health. Oftentimes, folks have to be reminded that [food] is our original medicine.”

At the heart of the tribes’ different approaches to food sovereignty is a shared common goal: reclaiming ancestral lands for habitat restoration, access to healthy, culturally relevant diets, and economic opportunity.

In Eureka, an Unprecedented Land Return—and the Restoration of Marine Habitats

Between California’s northern coastline and the redwood forests, the Wiyot Tribe has practiced its way of life for centuries, celebrating ceremonial dances on Tuluwat Island, its place of origin. The island sits in the Arcata Bay of the present-day city of Eureka and provided access to essential nourishment, including oysters, clams, mussels, and fish.

“For us, it’s a giant Costco. Everything that we needed was right there,” explained Ted Hernandez, Wiyot tribal chairman and cultural director, in a recent interview.

That was until 1860, when gold-rush era settlers ambushed and massacred between 80 and 250 Wiyots peacefully gathered on Tuluwat Island for a renewal ceremony. The surviving Wiyots were forced off the island and moved to Fort Humboldt, where Wiyots say that nearly half of the tribe died of exposure and starvation. They were then forcibly relocated to reservations at Klamath, Hoopa, Smith River, and Round Valley. In the early 1900s, a local church group bought land to house the Wiyots on what is known today as the Old Reservation. But after briefly losing federal recognition and a lack of potable water, the tribe moved to the Table Bluff Reservation, where it currently resides.

In 2000, after an acre and a half of the ancestral Tuluwat Island went up for sale, tribal elder Cheryl Seidner organized fundraisers to buy it for $106,000. This purchase gave the tribe momentum and hope that it could secure more land. Seidner led the Wiyots in negotiations with Eureka city leaders, and the city agreed to return most of the island to the tribe in 2019.

“With Tuluwat, it’s the first example of a city ever repatriating land to a tribe, which I think is great—but it’s also pretty sad that that never happens,” said Adam Canter, a natural resource specialist for the Wiyot Tribe.

Since then, the Wiyot people have used local community partners, volunteers, and state and federal resources to clean up the island, which was left in toxic disarray after years as the site of a shipyard for non-Native commercial fishermen. “There was a huge [Environmental Protection Agency] cleanup there,” said Canter, who leads the restoration effort. “The soil was contaminated with dioxins and pentachlorophenol oils, and all kinds of bad stuff.”

But this hasn’t deterred the Wiyots, who are 600 members strong and have a vision of restoring the crucial marine and land habitats that have for so long nourished the tribe. The Wiyots hope to improve health outcomes for tribal members and create a sustainable food system that emphasizes food sovereignty and security. “Now we’re in the process of completing that healing process by bringing back the traditional plants that were . . . in the waterways so our eels, and our oysters can grow back in the bay,” explained Hernandez. “And once that’s complete, then we can start the healing process for the whole world. But in order for us to do that, we need our traditional foods.”

Read the rest of the article at Civil Eats

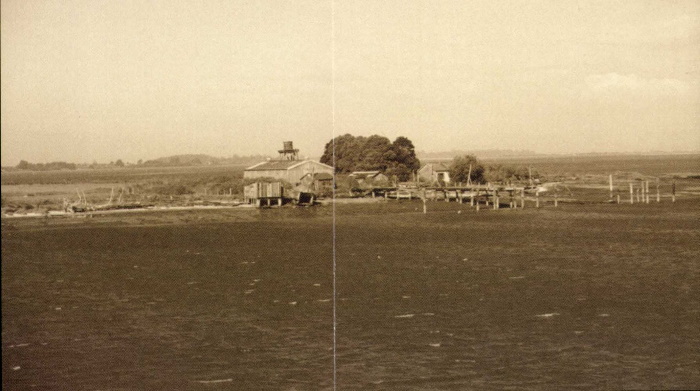

cover image: The first day of commercial fishing in 2019 on the Klamath River.

(Photo courtesy of the Yurok Tribe)

Truth Comes to Light highlights writers and video creators who ask the difficult questions while sharing their unique insights and visions.

Everything posted on this site is done in the spirit of conversation. Please do your own research and trust yourself when reading and giving consideration to anything that appears here or anywhere else.