Below the selected quotes you will find an article by John Waters as well as a video conversation between John Waters & Thomas Sheridan regarding the situation in Ireland, human consciousness, and unfolding global events.

“Thomas is a pagan and I am a Christian. We are friends. We seek, I believe, the same thing, which is not the triumph of one or other creed, but the restoration of Ireland’s transcendent imagination, without which Ireland — or any nation — cannot survive.”

~ John Waters (excerpt from article below)

“It’s all about the degeneracy of the establishment, the really bad stuff that goes on at the top, right? They’re constantly trying to normalize it to the rest of us.

“And I’m gonna make a prediction here. In the next few years they’re going to try and somehow, in some way, reduce the age of consent really low.”

[…]

“And you’re going to have it become integrated into songs and TV shows and sitcoms. This is the greatest battle we will face as a civilization…

“They want to bring the human race down to zero, below degeneracy. Why? It’s a transhumanist thing.

“Everything that makes a human a human — their natural sense of natural justice. They want to obliterate it.

“The whole lockdown was all about that…”

[…]

“Do you remember the question we all grew up with? How did the Holocaust happen? Now we know. Now we know.”

[…]

“What those people are capable of is projecting their own inner dysfunctionality on us, and then trying to normalize it. And I think they’re not finished yet.

“But it’s obviously a battle they’ve lost. It’s over. It’s not going to go that way. It won’t happen.”

[…]

“They’re inching towards it.

“Why the drag queen story time? What the hell is that all about? Why the need for that?

“The need for that is they’re sexualizing children on purpose. And that’s why the change in the school curriculums.

“We have to understand the wickedness of what we’re up against. It’s like we got a taste of it with the lockdowns. But that poison is still there. And we have to be vigilant about it…”

[…]

“And this is an important one for us: Don’t self-hex yourself.

“Just because they want transhumanism, don’t say, ‘Oh, we’re gonna get transhumanism’ or ‘They’re gonna do this. They’re gonna legalize that. They’re going to bring in mandatory…’.

“Don’t do that. And stay away from people who are nihilistic that way. Because you can actually self-hex that into reality. They want you doing that.

“So that’s a very important one. Don’t let them self-hex you anymore.”

~ Thomas Sheridan (excerpt from video below)

“It is our job — as people, as citizens, as parents, as sons and daughters, brothers and sisters — it is our job to begin to think about the process of reconstruction of our culture.

“With… these considerations in mind. How do we rebuild our culture so that we, our imagination, can expand rather than contract?

“How can it make us bigger in reality rather than smaller?

“How can it make us more confident rather than more afraid?

“How do we repossess our country?

“How do we become again as proprietors, not as slaves…?”

~ John Waters (excerpt from video below)

Our problem — our terminal problem — is that we have lost the capacity to walk upright in infinity. This will not be mended by pious ejaculations, any more than by neo-atheist bullshit.

by John Waters, John Waters Unchained

June 4, 2023

Video: A public conversation about the trajectory of the soul of Ireland between Thomas Sheridan and John Waters at the Tuatha Dé Danann festival in Fermoy, Co Cork, on Saturday May 27th, 2023.

(Readers of my weekly diary may already have read most of the following in my weekly diaries of last week and the week before — reproduced here by way of introducing the context and purpose of this event. The links to the video are at the bottom of the page.)

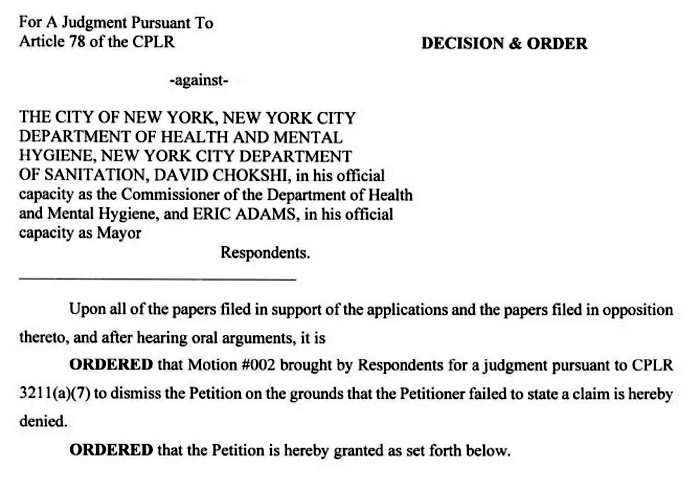

To say that the crisis of Ireland is ‘spiritual’ is not the same as saying that it is ‘religious’, though the difference can be hard to spell out unless it makes itself clear, as sometimes it does. Ireland has been undergoing a visible ‘religious’ crisis for perhaps 40 years, chiefly arising from a war of attrition on its primary faith-channel, Catholicism, by a cultural insurgency of indeterminate origin but rather obvious intentionality. The elements and episodes of this have already been well canvassed: culture wars, clerical hypocrisy, charges of child sexual abuse and its cover-up, and beyond that a failure on the part of the Catholic Church ‘corporate’ to offer a meaningful proposal for spiritual existence to generations supposedly educated in the values of the Enlightenment and the technological/technocratic age, culminating in its woeful and disgraceful conduct during the Covid episode, when it left its entire congregation bereft of guidance, accompaniment and leadership. Cumulatively, these factors, and multiple others, have delivered Ireland into a spiritual death-spiral that has yet to be formally identified, either by the society or any of its churches. The symptoms of this crisis can be traced in the drifts of Ireland’s cultural trajectory for many years, and the events of, in particular, the past decade, when Ireland as a nation and culture appeared to be galloping towards a cliff-edge of moral and existential self-destruction. Many of the relevant episodes and developments have been described and analysed on this platform over the past three years, and before that in several books of mine published since the mid-1990s, the most recent being the 2018 memoir, Give Us Back the Bad Roads.

It is clear that Ireland has now entered some kind of final stage of this unravelling, of which the consequences are unlikely to be confined to the wish-list of those who have been driving the culture wars. In other words, what will be lost will be not merely the Church, but the metaphysical perspective in its entirety. Like other nations, though in a rather more pronounced manner, Ireland has entered what feels terrifyingly like a death-spiral, not least in the context of its collapsing demographics and inability to tell victims from vanquishers, or differentiate between its responsibilities to its own people and its role in an international people-trafficking racket. That this collapse has long been disguised by spurious economic data and other propaganda will render its manifestation and effects all the worse when it finally hits.

This conversation, though unscripted, was loosely intended as an attempt to address these conditions in the context of Ireland’s long spiritual evolution, with a view to identifying some thread of continuity that might assist in reawaking the Irish soul before it comes too late to do so.

What follow are my initial thoughts written in advance of the event in Fermoy on May 27th, as published in my weekly Unchained diary.

Friday (May 26th)

As is customary in advance of such events, I am carrying around a bag of thoughts about this Saturday’s public conversation with Thomas Sheridan at the Tuatha Dé Danann festival in Fermoy. It is, of course, a Resistance event, beautifully choreographed by Gerry O’Neill (The West’s Awake, here on Substack), but for once I can banish any fears of an insurgency by left-wing actually existing fascists, since the venue is private and well secured. Democracy wins, for once — or so we hope. I shall give a full account of events here next week.

Our theme is (something like) the evolution of Ireland from paganism to Christianity, though that construction has an element of begging the question, if not actually beggaring it. It’s a broad enough canvas, and Thomas and I have already approached the territory in some of our private discussions, though by no means pushing towards anything resembling a plan. I think our instincts, though we approach from divergent positions, are very similar: We seek to find a true line through the pagan and Christian histories of this island that will take us to consideration of the meaning of the present moment and perhaps some suggestion of what the next phase might be like.

Thomas is a pagan and I am a Christian. We are friends. We seek, I believe, the same thing, which is not the triumph of one or other creed, but the restoration of Ireland’s transcendent imagination, without which Ireland — or any nation — cannot survive. Thomas is a great deal more knowledgable about the history of Irish spirituality than I am, and it remains to be seen whether my sense of things is accurate or sustainable, but I believe that, overall, the transition from paganism to Christianity was relatively seamless, that this augurs well for some form of ultimate reconciliation of the traditions, and that this ought to be our first point of departure. To put this another way: In terms of our spiritually imaginative collective journeying, we speak not of two histories, but one. The merging to be observed in the two strands far exceeds any sense of divergence, and this is reflected in innumerable contexts: our surviving sense of the significance of our ancient holy sites, our recently renewing consciousness of Celtic Christianity, our continuing reverence for the land and landscape of Ireland, and so forth. These factors tell us that there is a great deal more of paganism in our modern-day Catholic imagination than many Catholics might like to admit. I have no difficulty in admitting it, indeed celebrating it, although I confess I did not arrive at that point until I ran into Thomas Sheridan, about three years ago.

The core ‘belief’ that drives me here is that no society can endure unless it has a transcendent element to its collective imagination. That has been my obsession in writing about faith, spirituality and religion from the beginning, although for various reasons it has been all but impossible to communicate this in the cultural climate of recent decades. This, essentially, is the point of my books, Lapsed Agnostic (2007) and Beyond Consolation (2010), and also of a substantial segment of my 1997 book, An Intelligent Person’s Guide to Modern Ireland — in particular the chapter ‘On How God Has Been Kidnapped and Held to Ransom’.

In the first of his trilogy, Sacred Order/Social Order (2006-2008) — two volumes of which were published posthumously — the American Freudian, sociologist and cultural critic, Philip Rieff, posited that Western civilisation was in the third and likely final stage of a rise and fall that had occurred over the course of three millennia. At the heart of his thesis is the Freudian idea that only through sublimation of the sexual instinct had Western civilisation come about. In other words, controls and restrictions on sexual activity had, as it were, squeezed out of humanity the creativity and genius which begat Western civilisation. This, it will come as a surprise, was predominately a Christian innovation.

Many nowadays misunderstand Freud’s pronouncement that religion is ‘illusory’. This may have been, in a different sense, his private view, but his theoretical position was that religion is a form that creates the superstructure of a transcendent cultural understanding. This means that, in a sense, human beings, when present on Earth, are simply ‘moving through’ this dimension to another place, and hence direct a measure of their attention to what they intuit to be beyond the horizon. This, of course, is how most religions present matters also, though generally in a subtly different sense: Often, the purpose or effect is to persuade people to discount misfortune or grief in this life, in the expectation of an afterlife reward. But, in the Freudian and Rieffian senses, we speak not of foregoing joy on Earth, but of adopting a demeanour towards Earthly reality that maximises human functioning. In this way, mankind has been able to place itself within a transcendent order of being, which has enabled it to put to good use energy that might otherwise have been dissipated in licentiousness and depravity.

In his earlier works, such as Freud: The Mind of the Moralist and The Triumph of the Therapeutic, Rieff unwrapped his concept of the ‘psychological man’, a creature of late modern society, who essentially knew the existential cost of everything but the metaphysical value of nothing. Psychological man was the product of communities that had lost the positive values spawned by transcendent culture. Because the hope of salvation had been abandoned, therapy was all that remained.

In the first of his Sacred Order/Social Order trilogy, My Life Among the Deathworks, Rieff divides recent human history into three layers of religious evolution/devolution, which he identifies, somewhat confusingly, as ‘First World’, ‘Second World’ and ‘Third World’ cultures — resonating with the conventional contemporary understandings of these terms while conveying something much more enduring and fundamental. All societies, he claims, must espouse a sacred order, from which it derives authority to make laws and rules and give them the required force of moral injunctions seeking to outweigh other considerations. His ‘First World’ culture was essentially mythological: the Greek legends of gods and heroes, the ancient pagan world, the fables of the American ‘Indians’, the Irish stories of Cú Chulainn and the Tuatha Dé Danann. Such cultures were defined by a sense of Fate — which sees mankind at the mercy of forces greater than itself — and ordered by taboos.

In the ‘Second World’ culture, by Rieff’s hypothesis, this sense of Fate shifted to become a sense of Faith, with taboos replaced by commandments. This expands the transcendent imagination to embrace, as per the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the idea of man being governed by a specific God, and in some sense accompanied in his existence by this deity, which is accordingly imbued with a personalised meaning. The most significant element of this phase was the incarnation of Christ, in which God entered the earthly realm in order to ‘save’ mankind, which might be redefined as clarifying the purpose of human existence and elaborating a new way of being in the world. Both the First and Second Worlds are centred on a transcendent sense of reality, and obviously these are the phases in Irish history that Thomas and I will be seeking to reconcile or elucidate on Saturday.

But we will also, regrettably, have to come to the Third World phase, defined by Rieff as a culture exhibiting a social order that rests on no preexisting sacred order, characterised by artefacts and expressions that are invariably transgressive, debunking or deconstructive. This is the culture of ‘deathworks’, and is where we have now fetched up.

For the first time in history, cultural elites insist upon the untried, revolutionary idea that human society can flourish without sacred authority. ‘A culture of civility that is separated from sacred order has not been tried before,’ Rieff claimed in My Life Among the Deathworks, the first of his Sacred Order trilogy, published in 2006, the year of his death. Such cultures dispense with any interest in sublimating the instinctual carnality and lasciviousness of mankind, placing sexuality at the top of the totem pole, inverting the value systems acquired in the First and Second World phases, so that lust and hedonism become the dominant ‘values’, and their restriction deemed an offence against freedom. This amounts to a full 180 degree moral inversion from either or both of the first two cultural phases.

The pursuit of happiness through pleasure becomes the central obsession of a ‘Third World’ society. The accordant suppression of the sublimating tendency triggers the demolition of the transcendent order upon which the society will have been constructed in the first place, which hastens the termination of the metaphysical imagination of the society, and thereafter that of its citizens. What inevitably follows, according to Rieff, is a proliferation of sexual identities, the promulgation of pornograpjy and artistic deathworks, and attacks on the fundamental understandings of human nature. In this culture, what once was vice is now virtue, and what was virtue is scorned and laughed at. Pornography becomes the new ‘doctrine of value’, which is why it is to be pushed via the education system upon young children. In due course, such a society will inevitably overturn all of the taboos and limitations on sexual behaviour that once enabled the civilisation to come into being. These include squeamishness about paedophilia, bestiality and incest, as well as multiple categories of sexual ‘choices’, which facilitate their pioneer practitioners to become elevated into a form of hedonistic sainthood. Hence, for example, Panti Bliss, the iconoclast drag-queen grot-peddler as hero. Rieff calls this ‘anti-culture’, in which the objective is not to transmit constructive beliefs from generation to generation but to convey beliefs that cannot but destroy everything they touch. It becomes impossible, in such a society, to judge human behaviour by its transgressive aspects, because all prohibition is prohibited and — in Freudspeak, ‘all repression must be repressed’. In this culture, the only truth is that there is no truth; virtue is supplanted by vulgarity, and delicacy by degeneracy. A Third World culture has no memory, and repudiates all authority, and is ruled by fiction and theatrical role-playing.

It is not accidental that Rieff — who, incidentally, blames Freudian therapeutics for the unleashing of Third World culture — ended up labelling European and American culture as such. A deathwork he defines as a work of art that presents as ‘an all-out assault upon something vital to the established culture’, and a ‘culture of deathworks’ signifies the self-murder of a civilisation though filth and nihilism. What we now face, therefore, is not some random ‘culture war’ about particulars, but a radical divergence at the most fundamental level — a stifling of belief in the transcendent and its supplanting by a purely earthbound imagination, but which civilisation is rendered impossible to maintain.

His denunciation of ‘deathworks’ is not aesthetic, but a moral condemnation of the denigration of the sacred in art. He declared Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake as ‘the greatest third world literary creation’ on account of its demonstration of a method by which a cultural inheritance might be pulled apart and its pieces rearranged to produce a playful new culture that finds its forte in a mockery of, and freedom from, the old one. In this sense, the book is ‘liberatory’, because it shows a way to escape from the prescriptions and proscriptions of the sacred.

It can no longer be controversial to suggest that the defining characteristic of the present age might be diagnosed as the desire to subvert and destroy the institutions, traditions and beliefs that converged to become what is called Western civilisation — previously ‘Christendom’. This iconoclasm is carried out in the name of freedom — sexual freedom, for the most part — but is propelled by a fatal misunderstanding of the nature of reality and of the human structure.

Man is not built for the world — not entirely, at least. He cannot find satisfaction here, except in fits and starts, tantalising and brief. He is restless and searching, but cannot ever seem to find what he’s looking for. The optimal demeanour before this reality is, therefore, that of the existential nomad — always moving, not purely in the physical sense, but by adopting a mode of metaphysical impermanence, shifting constantly lest his searching lead to ennui.

In this sense, the cultural and societal inheritance of Christianity can be rinsed down to the idea that human happiness is better achieved by the sublimation of obvious desiring in the visualisation of a transcendent order of being. Man must live in the infinite, even while he is marooned in the three-dimensional. A functional culture in this sense requires a foundational mythology that enables it to transcend the state of continuous present time. This mythology relates to the past and to the putatively eternal future, and functions to render the present subservient to things higher and greater than itself. The nature of the rupture that has opened up in modern society has to do with the repudiation of this idea in favour of something that amounts to a culture rooted in itself and its own apprehended origins.

The Third World culture comes about when the means by which the civilisation was structured to begin with is forgotten, or overlooked, in a desire to destroy authority and tradition in the neurotic pursuit of the pleasures that have seemed to be gratuitously forbidden.

It is true that the resulting pseudo-culture can achieve the semblance of functionalism by mimicking the idea of a transcendent culture, since it maintains the outward appearance of a quasi-eternal perspective on reality. But this is actually an illusion, and all of the available artefacts (‘anti-art’) will reveal themselves as tautologies. A novel, for example, will not take its reader on a journey into the infinite, but will simply replicate the wider culture’s certitude that it amounts to all that is, and all that is necessary. Its aim is to achieve in the reader an accommodation with the proffered definitions, not to open up unlimited possibilities. It is possible to prolong the life of this pseudo-culture by the practice of parasitism upon that which it denies: an atheist poet, for example, may have derived inspiration from another whose work is rooted in the eternal, though he puts it to use to parody such understandings. A painting may mock the rejected inheritance, and yet derive its only life from what it derides.

Such a pseudo-culture is incapable of formulating any idea of the beautiful, the good or the true, because it renders man and his desire for immediate freedoms as the measure of all things. This culture remains oblivious that the untrammelled pursuit of the literal desiring of each and every human will in a short time lead to chaos, followed by outright destruction of everything. Very often, this phenomenon is ascribed to the waning of what is called ‘morality’ — to the applause of ‘progressives’ and the dismay of ‘conservatives’ — but this is a superficial reading. Really what is at play is the loss of the capacity to read reality as something to be ‘moved through’ on the way to another, imagined, place. The purpose is not, as Freud intimated, self-delusion, but the adoption of the optimal demeanour in a reality that does not meet the total scope of man’s desiring — indeed, while promising to satisfy the deepest cravings, leaves man bereft and humiliated in the wake of each lunging after the presumed object of his longing.

Anyway, to Fermoy! The foregoing touches on just a few of the thoughts I have been thinking as I cut the grass and tended to the security of the cabbage patch. In the evenings, I dipped into some of the late John O’Donoghue’s fabulous books — Anam Cara, Divine Beauty, Eternal Echoes, Bendictus — which offer such a rich repository of memory of those early years of what he called ‘Celtic Christianity,’ when our First World morphed into our Second. Now, reeling through the Third, it may be time to reconsider whether we wish to remain subject to the squalls and scudding of Fate, or whether we might wish to revisit some of the elements of our past culture(s) which gave us the riches we are now in the process of destroying.

Saturday (May 27th)

I had a friend one time whose wife was a bit contrary, so whenever she was rude or abrupt with someone, he would take them aside and explain: ‘She wasn’t born on a sunny day.’

But I was born on a sunny day, and every one of my 67 birthdays has fallen on such a day, and that’s my story and I’m sticking to it. Every birthday from my childhood comes back to me in a flood of sunlight and me walking to school, slightly less reluctantly than other days, past the May altars and across the bridge above the drying-up riverbed, with my jumper tied around my waist. I remember only one darkish day, and this purely metaphorically, when I passed an old man sitting breathlessly on a doorstep, out of the sunlight. He lived in a ramshackle cottage with a thatched roof beside the railway bridge on the Trien road, and when I came home at lunchtime my mother told me he had died. His name was Jack Tighe. That was at least 55 years ago, and I have never forgotten the shock of being so close to a dying man.

Today is a sunny day in Tipp. It is not my birthday but the day before my birthday. Out of the blue, it is the most perfect day of the year so far. Jesus is smiling on the Resistance, for he has moved the weather of my birthday one day forward to ensure that the Tuatha Dé Danann festival in Fermoy goes off well.

So, I have awoken in a B&B in the valley of Poulaculleare (Poll An Chóiléir — ‘the hole of the collar’, I think), in the heart of south Tipperary, some 20 miles from Fermoy, and am sitting outside waiting for my lift. The Tuatha Dé Danann Festival is the brainchild of the powerhouse that is Gerry O’Neill (the West’s Awake — and how!) and today is its debut, the first of what we hope will be many more such events, though we barely dare to think so for fear of hexing things.

As relayed last week, I am booked to speak at the festival this afternoon, along with Thomas Sheridan, about the state of the soul of Ireland at this moment in its long spiritual journey from paganism, via Celtic Christianity, to whatever we’re going through now. Our title is ‘The Awakening Soul of Ireland’, which is appropriately hopeful, though possibly a bit premature.

As I outlined last week, I see this spiritual trajectory as a climb towards and then a falling away from transcendence, exactly in the fashion described by the American sociologist, Philip Rieff, in his 2006 book, My Life Among the Deathworks. It’s a risky enough theme to be discussing in front of a mixed audience, because, as I have discovered over the years, when it comes to ‘religious’ topics, people tend to hear — or not hear — only their own prejudices, so in some respects you are wasting your time trying to break new ground.

Whether Thomas and I were successful in this endeavour, I shall leave in the hands of you, the reader. I believe we opened some interesting new boxes, and certainly the response afterwards was encouraging. But people should not approach the video with prior assumptions and expectations, for what we are doing is not evangelising or engaging in personal testimonies, but seeking to explore how the decrepit transcendent imagination of the nation might be restored to good order.

This is for me the core meaning of that much-used term, ‘the spiritual war’. Had our transcendent imagination remained strong, we should not have ended up as baaing sheep, taking orders from smirking simpletons and behaving in a manner as to cause the lights of our civilisation to go out, one by one, with no let-up or remission for three years and counting. It is confusion as to our meaning and purpose that ultimately causes this degree of demoralisation. And, yes, the churches — worst of all the Catholic Church — played a massive part in this, selling the pass on freedom, without which there is no possibility of retaining truth and justice at the heart of public affairs.

It is necessary to tread carefully through these topics, but hopefully not too carefully. Mostly, religious-minded people attend talks ‘about religion’ to be affirmed in their own certitudes, just as people who have persuaded themselves that it is all nonsense gravitate to such discussions to disrupt them with ridicule and nonsense. I’m not interested in catering for either party. Both a dog-in-the-manger approach to faith by the faithful, and the dumbass neo-atheism of the past couple of decades have contributed to bringing us to this darkest of places. Everyone needs to remember that fixing what is broken will involve talking in a language that as many as possible can relate to. There is no point preaching to choirs, and anyone coming to such discussions to hear what they already know and believe is wasting at least his own time.

The same goes for those who dismiss religion out of hand, even those who say they can ‘find their own way to God’. Maybe they can, but what about if there had never been any conduit for religious ideas in their culture, which is what’s going to obtain from now on? It’s a little like the residents of Dun Laoghaire/Rathdown, who have recently been congratulating themselves on their ‘performance’ in Census 2022 on account of the fact that they had the highest showing for ‘no religion’ in the country, at 24 per cent. Probably the most schooled and the least intelligent region of the country (I live there, so I can say this with some conviction), DL/R fails to comprehend that its irreligious disposition, being for now a luxury of a community with residual faith traces, will one day flip and hit its population for six, when critical mass is reached and the smug secularists cotton on that they have delivered their descendants into a hellhole of pitilessness and unhope.

And I have as little patience with those who dismiss all these vital questions with an ‘Oh it’s all just a means of control!’ as I do with Holy Joes who tell me there is a fixed protocol by which I must pursue my spiritual life. A chap was trying to do this to me yesterday as myself and Thomas and Louise Roseingrave were sitting outside trying to get our thoughts together (I mean collectively) for our event. He purported to be ‘having a conversation’, but he was just showering me with questions from behind his veil of cigarette smoke: ‘Why do you say that?’; ‘What do you mean by that?’; ‘Yes, but how do you actually know that?’; et cetera, like a teacher trying to draw the correct answer from a child. In the end I got tired of this socratic dialogue and told him to take a running one. It’s hard to blame him. This is what has passed for conversation in modern media: some dumbass trying to stop you talking by peppering you with smart-sounding questions that actually amount to prohibitions because they stop you saying what you want to say. Essentially, it’s a form of silencing, which is generally what you get if you’re stupid enough to go on with one of the elite mediocrities posturing as moderators of our national conversation.

But just repeating the same mantras about religion being no more than a control grid amounts to the same thing, blocking off any meaningful conversation.

We have heard nothing for about 40 years except the excesses and downsides of religion. We hear rather less about what we have lost by ceasing to speak about the good it has wrought in the world, which is far from trivial. It’s time to move beyond cliches, of either polarity. Unless we’ve been exiled on Mars, we know all about the bad stuff, but can we occasionally discuss the possibility that there are positive reasons why societies might cherish religious ideas?

I noticed a few people walked out quite early on from today’s event featuring Thomas and me. That’ll be the Holy Josephines, I figured, ‘offended’ because I’m making jokes about Jesus coming in a taxi from Cork airport, but unlikely to arrive. (He never arrived, as I predicted.) I don’t do this gratuitously. I do it to send signals to the wanderer that there might be something here worth listening to, that what’s afoot is not an in-house prayer meeting. The suggestion that God might have a sense of humour is never a bad place to begin.

Our problem — our terminal problem — is that we have lost the capacity to walk upright in infinity. This will not be mended by pious ejaculations, any more than by neo-atheist bullshit. It will only become capable of treatment when people can be persuaded to listen to and participate in honest conversations about the meaning of life: Why are we here? Is there even a reason? What can we know about any of this? Those who dismiss those questions because, like Alastair Campbell, they ‘don’t do religion’ are shooting their own children in the feet and hands. Everyone has a right to hear how this stuff might be useful to them. The idea that each of us can arrive at our own spiritual understandings is delusional, because none of us would have the first notion of any of this had we not received a grounding — however imperfect — in a specific religious worldview. Our sole ‘religion’, in that case, would be something like communism, which is what our grandchildren will get unless we can turn things around.

When I speak of these matters, in the general or Christian contexts, I sometimes speak of ‘mythology’, which also drives the Holy Joes mad because they do not understand what mythology is and imagine that what I’m saying is that Christianity is ‘made up’. For the purposes of these discussions, I say that it may or may not be, but that either way the issue is beside the point, which is that these questions belong to an entirely different part of the human imagination, in which things can be true and allegorical at the same time. I have in mind ‘myth’, in the Greek sense of public dreams and stories that are truer than history, larger than facts and more real than what’s on the news.

Several times in the course of my contributions today, I stressed that I was not here to talk about my personal beliefs, but of the possibility of restoring a sense of the transcendent to our public conversations. I have often found that people seem not to see this distinction, imagining that you are preaching or evangelising when in fact you are trying to speak of what is, in this context, fundamentally a cultural question, carrying different implications for the collective than for the personal realm.

In his 1971 volume, Myths to Live By, a collection of lectures delivered at the Cooper Union Forum in New York, between 1958 and 1971, the great mythological scholar, Joseph Campbell, set out the superstructure of mythology in human culture and history. He noted that, from their earliest established existence, hundreds of years before Christ, human myths were concerned primarily with two central themes: the adaption to and enablement of the flourishing of the social groups that give life and protection to the individual, and transcendence of the mortal condition. In a sense, these two themes become one, because both aim for the creation of understandings that allow a human life to extend beyond its mortal boundaries. Campbell described the same mythological patterns in multiple primitive societies — the same themes, symbols, meanings and essential stories. The story of the Garden of Eden, for example, is to be found in the origins of Buddhism in Japan, some 1,000 years before the Book of Genesis was written.

All civilisations tend to take their own mythologies literally, and these beliefs, usually transmitted by religion, have been the very buttresses of multiple civilisations, supporting moral order, cohesion, vitality and imagination. Myth enables us to exceed our own expectations of ourselves by drawing on the deeper capacities which the banality of the everyday contrives to suppress. Successful civilisations, therefore, tend to be the ones that take their own mythologies seriously but not wholly literally. The more a society moves towards rationalism, the more it risks disequilibrium by virtue of no longer holding fast to its founding and sustaining mythologies. Human life, as Nietzsche told us, depends for its propulsion on illusions. The loss of belief in the founding myths provokes uncertainty and the collapse of values and moral order, leading eventually to decay and degeneracy. This is where we have now fetched up.

Campbell elaborates: ‘With our old mythologically founded taboos unsettled by our modern sciences, there is everywhere in the civilised world a rapidly rising incidence of vice and crime, mental disorders, suicides and dope addictions, shattered homes, impudent children, violence, murder, and despair.’

Mythology, as Campbell insisted, is not for the entertainment of children, but nor is it for scholars only. It is a matter of the utmost importance to human society — ‘For its symbols (whether in the tangible form of images or in the abstract form of ideas) touch and release the deepest centers of motivation, moving literate and illiterate alike, moving mobs, moving civilizations.’

And again: ‘The rise and fall of civilizations in the long, broad course of history can be seen to have been largely a function of the integrity and cogency of their supporting canons of myth; for not authority but aspiration is the motivator, builder, and transformer of civilization.’ We take for granted that this is true of the Ancient Greek and Roman empires, but we rarely think of our own civilisation in the same way. We, after all, are ‘modern,’ which somehow puts us into a different category.

And this provokes a question: Is it possible for a society to modernise and remain credulous as to its founding myths? Is there a way by which myths can be retained as something akin to beliefs, even while their literalness is being debunked?

Joseph Campbell held that the decline of belief in myth arises from over-literal belief in religious ideas. Mythology he defined as ‘other people’s religion’: the ‘penultimate truth — penultimate because the ultimate cannot be put into words.’ Religion, he believed, can give rise to popular misunderstandings of the nature of mythology. Half the world, he said, thinks that what he called ‘the metaphors of religious traditions’ are facts, and the other half insists that they are lies.

This is exactly the problem. Over the past couple of decades, the world has seemed to come under sustained attack from the neo-atheists — Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens to the fore — in what had all the signs of a psy-op, i.e., a cultural insurgency designed to weaken the foundations of our religious underpinnings. In some respects, Philip Rieff’s analysis of the three stages of the spiritual growth and decay of societies gives us a clearer viewfinder in which to observe the problem, which is actually as Campbell has stated it. Rieff’s concept of ‘Second World’ modes of belief, for all kinds of arcane and elusive reasons, seems less well adapted to the retention of metaphysical values in culture than the First World kind, which enables a less literal form of attachment to the guiding stories of the belief-system. Abrahamic religion demands a substantialist engagement with the figures and stories of the canon, to which we are enjoined to apply the same forms of reason as to everyday matters. This has proved fatal to the plausibility of, for example, the Christian narrative, which seems to occupy a rather unique situation in being increasingly difficult to sustain at the mythological level once literal belief begins to wane.

Another factor is that ancient mythological understandings tended to be mixed up with tribal sentiment, which meant that their heroic qualities superseded consideration of literal meaning. Because our Western understanding of mythology is so limited and so literal, and because our cultures no longer remind us of such elemental circumstances, we think of our ‘myths’ — those things that ancient human cultures assumed to be truer than the truth — as dispensable in the manner of gramophones or telegraphs. This may be our fatal mistake.

For these and other reasons, ‘modern’ society became — in its own mind — too ‘clever’ for the God it had been reared to see as its Maker. Really, the problem was not one of an excess of intelligence, but an inability to comprehend things simultaneously in different frames, which may be a symptom of a deficit of intelligence.

It is a strange quirk of what we think of as ‘modern’ society that it sees its own crude literalism as evidence of increased enlightenment. But, as Campbell advised, ‘Gods suppressed become devils.’ In other words, we deal here with a stark polarisation of options: once pursuit of ‘The Good’ is set aside as a driving mechanism, it is soon supplanted by its antithesis: the pursuit of depravity and evildoing.

In Hero With A Thousand Faces, Campbell wrote: ‘The psychological dangers through which earlier generations were guided by the symbols and spiritual exercises of their mythological and religious inheritance, we today (in so far as we are unbelievers, or, if believers, in so far as our inherited beliefs fail to represent the real problems of contemporary life) must face alone, or, at best with only tentative, impromptu, and not often very effective guidance. This is our problem as modern, “enlightened” individuals, for whom all gods and devils have been rationalized out of existence.’

But it’s worse than that: the devils have been able to present themselves as heroes. As Campbell emphasised, the effect of a living mythological symbol is to waken and give guidance to the energies of life. It ‘turns us on’ and allows — motivates — us to function in a mode of animated engagement with reality. It appropriates the dormant energies of body and mind, and harnesses them to particular ends. This has served our cultures well for the two thousand years of the Christian era, itself built on the strong foundations of the paganism that came before. But, as Campbell also tells us, when these stories no longer seem true, the symbols no longer work their magic, and man, individual by individual, ‘cracks away’ from the group, becoming dissociated, disoriented and alienated. This is what we are confronted with in what we call ‘post-Christian society’. The ‘affect symbols’ which once summoned each individual member of the belief system to the same purpose now ring hollow, and have not been replaced by anything capable of summoning up the same degree of affective engagement with reality.

My objective in as far as this model of the discussion is concerned is not to restore the claims of this or that religion, or even of religion in general, but simply to remind myself and others that the human mechanism is anything but simple, and we should ponder carefully before abandoning or jettisoning things that have proved useful. Progress can take us backwards, not because it is ‘bad’, but because history does not see things in black and white, good and bad. History, like nature, is red in tooth and claw. It was never a given that the imagined nature of progress emanating from the human mind was going to be maximally suited to the biological, animal nature of man himself. In many ways, the fruits of his own genius impact on him more like the actions of a colonising, occupying power. He thinks he has to follow every conceivable thread of progress and invention, unable to consider whether or not it is good for him, or even if it might destroy him. And, all the while, his moral genius lags behind his capacity for technical invention.

Three years ago, it began to dawn on some of us that the Covid mission was an attempt to restore the terrors, and their supposed remedies, that religions emerged as an answer to — terror of death, first and foremost. Under the control of the godless, the culture now moves to take advantage of the destruction of religion, preying upon the hapless post-Christian refugees from what they imagine to be unreason. Covid is an anti-religion in this precise sense: it seeks to restore man to his primal state, before the thought of God ever crossed his countenance.

There was one significant disruption to our onstage conversation today, by a heckler or interloper who made an attempt to throw the discussion near the end, though I am told by the videographers that this will not feature in the recording, as the voice of the interloper cannot be heard on the tape, and in any event it caused the discussion to break away briefly into a series of tangents. I confess I could not hear him so clearly either, but I gathered that his point was that we were not being ‘positive’ enough. I utterly hate that kind of nonsense — as if we have a responsibility to be ‘positive’ no matter how dark it gets. As it happens — and as I pointed out to the heckler — I had just a couple of minutes earlier said that I believed we were winning the war, to which he rejoined along the lines of ‘What war? There’s no war.’ I believe it was at this point that Thomas asked him if he was a civil servant — an excellent question, which caused the interloper to stutter and stall, before resuming his incoherent interruption. In due course he was persuaded to sling his hook, and off he went with a smug smirk on his chops. My sense is that he was a Guardstapo agent, possibly the one who had spent the week trying to find ways of making things awkward for Gerry O’Neill and his team by ringing up asking about traffic management plans, planning regulations, and so forth. No doubt, like every other agent provocateur we encounter in our country these days, he was in the pay of ‘the PR agency from Hell’, which has been managing the innumerable psy-ops perpetrated against Irish society for the past dozen years. In any event, he achieved almost nothing, and the whole shemozzle lasted about a minute and a half.

The event was held in the grounds of a fabulous old house not far from Fermoy town centre. It is a heavenly place, the property of a local family, well-disposed towards the Resistance. Looking around the site this evening, with its campsite on the hill facing the front door, the marquee in the back garden, and the various food and craft stalls dotted around, it struck me that it was a small-scale version of the Lisdoonvarna music festival of the early 1980s — the same spirit, or something like it, the same categories of people (life-embracing, joyous, freedom-loving), the same implicit sense of Ireland as a unique culture in the world, something worth loving and preserving. Leaving this evening, I had a positive feeling that this is something that will expand because we are — dread cliche! — ‘on the right side of history’, and because Ireland longs to live, and those seeking to destroy her know only death, and so have nothing to propose to her now or in the future. It will, I felt certain as we drove away, become possible to heal and restore our broken culture, and in doing so reclaim our country from the jaws of extinction.

Original video available at YouTube. [Mirrored at Odysee below.]

Connect with John Waters

France is not run by representatives of the French people, but by representatives of the global money power, the criminal gang which owns pretty much everything, everywhere.

France is not run by representatives of the French people, but by representatives of the global money power, the criminal gang which owns pretty much everything, everywhere.