According to Alexandra Latypova, an ex-pharmaceutical industry executive, documents obtained from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine suggest the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Moderna colluded to bypass regulatory and scientific standards used to ensure products are safe.

by Megan Redshaw, The Defender

July 12, 2022

According to an ex-pharmaceutical industry and biotech executive, documents obtained from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine suggest the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Moderna colluded to bypass regulatory and scientific standards used to ensure products are safe.

Alexandra Latypova has spent 25 years in pharmaceutical research and development working with more than 60 companies worldwide to submit data to the FDA on hundreds of clinical trials.

After analyzing 699 pages of studies and test results “supposedly used by the FDA to clear Moderna’s mRNA platform-based mRNA-1273, or Spikevax,” Latypova told The Defender she believes U.S. health agencies are lying to the public on behalf of vaccine manufacturers.

“It is evident that the FDA and NIH [National Institutes of Health] colluded with Moderna to subvert the regulatory and scientific standards of drug safety testing,” Latypova said.

“They accepted fraudulent test designs, substitutions of test articles, glaring omissions and whitewashing of serious signs of health damage by the product, then lied to the public on behalf of the manufacturers.”

In an op-ed on Trial Site News, Latypova disclosed the following findings:

- Moderna’s nonclinical summary contains mostly irrelevant materials.

- Moderna claims the active substance — mRNA in Spikevax — does not need to be studied for toxicity and can be replaced with any other mRNA without further testing.

- Moderna’s nonclinical program consisted of irrelevant studies of unapproved mRNAs and only one non-GLP [Good Laboratory Practice] toxicology study of mRNA-1273 — the active substance in Spikevax.

- There are two separate investigational new drug numbers for mRNA-1273. One is held by Moderna, the other by the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases within the NIH, representing a “serious conflict of interest.”

- The FDA failed to question Moderna’s “scientifically dishonest studies” dismissing an “extremely significant risk” of vaccine-induced antibody-enhanced disease.

- The FDA and Moderna lied about reproductive toxicology studies in public disclosures and product labeling.

“Moderna’s documents are poorly and often incompetently written — with numerous hypothetical statements unsupported by any data, proposed theories, and admission of using unvalidated assays and repetitive paragraphs throughout,” Latypova wrote.

“Quite shockingly, this represents the entire safety toxicology assessment for an extremely novel product that has gotten injected into millions of arms worldwide.”

Finding 1: Moderna’s non-clinical summary contains mostly irrelevant materials.

According to Latypova, about 80% of the materials disclosed by HHS that FDA considered in approving Moderna’s Spikevax pertain to other mRNA products unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19.

“Approximately 400 pages of the materials belong to a single biodistribution study in rats conducted at the Charles River facility in Canada for an irrelevant test article, mRNA-1674,” Latypova said. “This product is a construct of 6 different mRNAs studied for cytomegalovirus in 2017 and never approved for market.”

Latypova said the study showed lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) distribute throughout the entire body to all major organ systems.

Latypova found it odd the study protocol, report and amendments related to the study were copied numerous times throughout the HHS documents, suggesting Moderna may have been trying to meet a minimum word count.

In between the repetitive copies of the “same irrelevant study,” Latypova found “ModernaTX, Inc. 2.4 Nonclinical Overview” for Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine with the investigational new drug application reference IND #19745.

Module 2.4, she said, is a standard part of the new drug application and is supposed to contain summaries of nonclinical studies.

Latypova wrote:

“There are three separate versions of Module 2.4 included and many sections appear to be missing. It is not clear why multiple versions are included and there is no explanation provided as to which version specifically was used for the approval of Spikevax by the FDA.”

Latypova noted all three copies of Module 2.4 appear to have the same overview but reference a different set of statements and studies.

Latypova said the description of the finished supplied product differs between the two versions:

“Version 1 (p. 0001466) [says] mRNA-1273 is provided as a sterile liquid for injection at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in 20 mM trometamol (Tris) buffer containing 87 mg/mL sucrose and 10.7 mM sodium acetate, at pH 7.5.

“Version 2 (p. 0001499) [says] the mRNA-1273 Drug Product is provided as a sterile suspension for injection at a concentration of 20 mg/mL in 20 mM Tris buffer containing 87 g/L sucrose and 4.3 mM acetate, at pH 7.5.”

“It appears from reading section 2.4.1.2 Test Material (p.0001499) that Version 2 of the drug product had been used for manufacturing the Lot AMPDP-200005 which was used for nonclinical studies,” Latypova said. But “there is no explanation given for why the drug product in version 1 is different, and no comparability testing studies between the two product specifications are provided.”

Latypova pointed out that the package insert for FDA-approved Spikevax does not contain any information regarding the concentration of the product supplied in its vials.

Finding 2: Moderna said Spikevax mRNA does not need to be studied for toxicity and can be replaced with any other mRNA without further testing.

Latypova alleges Moderna, Pfizer and Janssen — manufacturer of the Johnson & Johnson shot — along with the FDA, have been deceptive in their assertions claiming the risks of COVID-19 vaccines are associated with the LNP delivery platform, and therefore, the mRNA “payload” does not need to undergo standard safety toxicological tests.

The documents state:

“The distribution, toxicity, and genotoxicity associated with mRNA vaccines formulated in LNPs are driven primarily by the composition of the LNPs and, to a lesser extent, by the biologic activity of the antigen(s) encoded by the mRNA. Therefore, the distribution study, Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)-compliant toxicology studies, and in vivo GLP-compliant genotoxicity study conducted with mRNA vaccines that encode various antigens developed with the Sponsor’s mRNA-based platform using SM 102-containing LNPs are considered supportive and BLA-enabling for mRNA-1273.”

Moderna is “claiming that the active drug substance of a novel medicine does not need to be tested for toxicity,” Latypova said. “This is analogous to claiming that a truck carrying food and a truck carrying explosives are the same thing. Ignore the cargo, focus on the vehicle.”

Latypova called the claim “preposterous,” as mRNAs and LNPs separately and together are “entirely novel chemical entities” that each require their own IND application and data dossier filed with regulators.

“Studies with one mRNA are no substitute for all others,” she added.

According to the European Medicines Agency, this chemical entity is entirely novel:

“The modified mRNA in the COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine is a chemical active substance that has not been previously authorized in medicinal products in the European Union. From a chemical structure point of view, the modified mRNA is not related to any other authorized substances. It is not structurally related as a salt, ester, ether, isomer, mixture of isomers, complex or derivative of an already approved active substance in the European Union.

“The modified mRNA is not an active metabolite of any active substance(s) approved in the European Union. The modified mRNA is not a pro-drug for any existing agent. The administration of the applied active substance does not expose patients to the same therapeutic moiety as already authorized active substance(s) in the European Union.

“A justification for these claims is provided in accordance with the ‘Reflection paper on the chemical structure and properties criteria to be considered for the evaluation of new active substance (NAS) status of chemical substances’ (EMA/CHMP/QWP/104223/2015), COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine is therefore classified as a New Active Substance and considered to be new in itself.”

“The reviewers specifically stated ‘modified RNA’ and not just the lipid envelope constitute the new chemical entity,” Latypova said. “All new chemical entities must undergo rigorous safety testing before they are approved as medicinal products in the United States, European Union and the rest of the world.”

Latypova said Moderna failed to cite any studies showing “all toxicity of the product resides with the lipid envelope and none with the payload” of the type and sequence of mRNA delivered to various tissues and organs.

“It is also not a matter of a mistake or rushing new technology to market under crisis conditions,” she added. “This scientifically fraudulent strategy was not only premeditated, it was also never really concealed.”

Latypova gave the example of a 2018 PowerPoint presentation by Moderna CEO Stéphane Bancel at a JP Morgan conference where he stated: “If mRNA works once, it will work many times.”

“This describes the deception practiced by the manufacturers, FDA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), NIH and every government health authority or mainstream media talking head who participated in it,” Latypova said.

She continued:

“Imagine Ford Motor Company claiming that its crash testing program should be contained to the vehicle’s tires and that one test is sufficient for all vehicle models.

“After all both F150 and Taurus have tires, what’s in between the tires ‘worked once and will work again,’ and therefore it is inconsequential to safety, does not need to be separately tested and can be replaced at the manufacturer’s will with any new variation.

“This is the claim that Moderna, Pfizer, Janssen and other manufacturers of the gene therapy ‘platforms’ have utilized. Unlike Ford’s products, theirs have never worked as none of their mRNA-based gene therapy products have ever been approved for any indication. The fact that the regulators did not object to this argument raises an even greater alarm.”

“There is no question of incompetence or mistake,” Latypova said. “If this represents the current ‘gold standard’ of regulatory pharmaceutical science, I have very bad news regarding the safety of the entire supply or new medicines in the U.S. and the world.”

Finding 3: Moderna’s nonclinical program included only one non-GLP toxicology study of the active substance in Spikevax.

According to Latypova, a non-clinical program for a novel product usually includes information on pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, safety pharmacology, toxicology and other studies to determine the carcinogenicity or genotoxicity of a drug and its effects on reproduction.

The more novel the product, the more extensive the safety and toxicity evaluations need to be, she said.

In Module 2.4 described above, Latypova was able to identify 29 unique studies but only 10 were done with the correct mRNA-1273 test particle. The other studies were conducted using a “variety of unapproved experimental mRNAs unrelated to Spikevax or COVID illness.”

For example, the in-vivo genotoxicity studies included an irrelevant mRNA-1706 and a luciferase mRNA that is not in Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine.

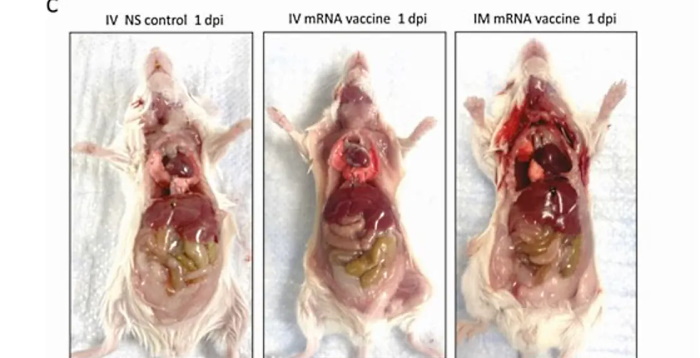

“Of the 10 studies using mRNA-1273, nine were pharmacology (‘efficacy’) studies and only one was a toxicology (‘safety’) study,” Latypova said. “All of these were non-GLP studies, i.e., research experiments conducted without validation standards acceptable for regulatory approval.”

There was only one toxicology study included in Moderna’s package related to the correct test particle mRNA-1273, but the study was non-GLP compliant, was conducted in rats and was not completed at the time the documents were submitted to the FDA for approval.

The results of the study were indicative of possible tissue damage, systemic inflammation and potential severe safety issues — and they are also dose-dependent, Latypova said. Moderna noted its findings but “simply moved on, deciding to forgo any further evaluation of these effects.”

Regarding reproductive toxicology, the only assessment was conducted on rats.

Pharmacokinetics — or the biodistribution, absorption, metabolism and excretion of a compound — were not studied with Moderna’s Spikevax mRNA-1273.

“Instead, Moderna included a set of studies with another, unrelated mRNA-1647 — a construct of six different mRNAs which was in development for cytomegalovirus in 2017 in a non-GLP compliant study,” Latypova said. “This product has not been approved for market and its current development status is unknown.”

Moderna claimed the LNP formulation of mRNA-1647 was the same as in Spikevax, so the study using this particle was “supportive of” the development of Spikevax.

“This claim is dishonest,” Latypova said. “While the kinetics of the product may be studied this way, the toxicities may not!”

She explained:

“We do not know what happens with the organs and tissues when the delivered mRNA starts expressing spike proteins in those cells. This is a crucial safety-related issue, and both the manufacturer and the regulator were aware of it, yet chose to ignore it.

“The study demonstrated that the LNPs did not remain in the vaccination site exclusively, but were distributed in all organs analyzed, except the kidney. High concentrations were observed in lymph nodes and spleen and persisted in those organs at three days after the injection.

“The study was stopped before full clearance could be observed, therefore no knowledge exists on the full time-course of the biodistribution. Other organs where vaccine product was detected included bone marrow, brain, eye, heart, small intestine, liver, lung, stomach and testes.”

Given that LNPs of the mRNA-1647 were detected in these tissues, it’s reasonable to assume the same occurs with mRNA-1273 and “likewise would distribute in the same way,” Latypova said. “Therefore the spike protein would be expressed by the cells in those critical organ systems with unpredictable and possibly catastrophic effects.”

“Neither Moderna nor FDA wanted to evaluate this matter any further,” she added. “No metabolism, excretion, pharmacokinetic drug interactions or any other pharmacokinetic studies for mRNA-1273 were conducted,” nor were safety pharmacology assessments for any organ classes.

Finding 4: ‘Serious conflict of interest’ exists between Moderna and NIH.

According to Latypova, Moderna’s documents contain a letter from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases authorizing the FDA to refer to IND #19635 to support the review of Moderna’s own IND #19745 provided in “Module 1.4.”

Although Module 1.4 was not included in the documents provided by HHS, the FDA on Jan. 30 revealed the following timeline for Moderna’s Spikevax.

According to the FDA, Spikevax has two sponsors of its IND application package, including the NIH division that reports to Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and chief medical advisor to President Biden.

The date of the pre-IND meeting for Spikevax was on Feb. 19, 2020. The IND submission for the NIH’s IND was on Feb. 20, 2020, while Moderna’s own IND was submitted on April 27, 2020.

According to the CDC, as of Jan. 11, 2020, Chinese health authorities had identified more than 40 human infections as part of the COVID-19 outbreak first reported on Dec. 31, 2020.

The World Health Organization on Jan. 9, 2020, announced the preliminary identification of the novel coronavirus. The record of Wuhan-Hu-1 includes sequence data, annotation and metadata from the virus isolated from a patient approximately two weeks prior.

Latypova said this raises several questions warranting further investigation:

- Preparation for a pre-IND meeting is a process that typically takes several months, and is expensive and labor-consuming. How was it possible for the NIH and Moderna to have a pre-IND meeting for a Phase 1 human clinical trial scheduled with the FDA for a vaccine product a month before the COVID-19 pandemic was declared?

- “How was it possible to have all materials prepared and the entire non-clinical testing process completed for this specific product related to a very specific virus which was only isolated and sequenced (so we were told) by Jan. 9, 2020?”

- Ownership of the IND is both a legal and commercial matter, which in the case of a public-private partnership, must be transparently disclosed. “What is the precise commercial and legal arrangement between Moderna and NIH regarding Spikevax?”

- “Does NIH financially benefit from sales of Moderna’s product? Who at NIH specifically?”

- “Does forcing vaccination with the Moderna product via mandates, government-funded media campaigns and perverse government financial incentives to schools, healthcare system and employers represent a significant conflict of interest for the NIH as a financial beneficiary of these actions?”

- “Does concealing important safety information by a financially interested party (NIH and Moderna) represent a conspiracy by the pharma-government cartel to defraud the public?”

Latypova further noted that immediately after the pre-IND meeting with the FDA, an “extremely heavy volume of orders for Moderna stock” began to be placed in the public markets.

This warrants an “additional investigation into the investors that were able to predict the spectacular future of the previously poorly performing stock with such timely precision,” she said.

Finding 5: FDA failed to question Moderna’s ‘scientifically dishonest studies’ dismissing an ‘extremely significant risk’ of vaccine-induced antibody-enhanced disease.

Moderna, prior to 2020, had never brought an approved drug to market.

“Its entire product development history was marked by numerous failures despite millions of dollars and lengthy time spent in development,” Latypova said. “Notably, its mRNA-based vaccines were associated with the antibody-dependent-enhancement phenomenon.”

For example, Moderna’s preclinical study of its mRNA-based Zika vaccine in mice showed all mice “uniformly [suffered from] lethal infection and severe disease due to antibody enhancement.”

The scientists were able to develop a type of vaccine that generated protection against Zika that “resulted in significantly less morbidity and mortality,” but all versions of the vaccine unequivocally led to some level of antibody-dependent-enhancement.

The Primary Pharmacology section for Spikevax includes nine studies evaluating immunogenicity, protection from viral replication and potential for vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease.

“These studies included the correct test article (mRNA-1273), however, all were non-GLP compliant,” Latypova said. The results of these studies are briefly summarized in the text of the document package, yet the study reports are not provided.

In the disclosed documents, Moderna claims “there were no established animal models” for SARS-CoV-2 virus due to its extreme novelty.

Yet, in the next sentence, “despite the extreme novelty of the virus,” Ralph Baric, Ph.D., at the University of North Carolina possessed an already mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 virus strain and provided it for some of Moderna’s studies, Latypova said.

According to Latypova’s assessment, there were other numerous contradictions in Moderna’s documents, and when enhanced disease risk was revealed in assays, the company waived off its own results with a statement regarding the invalidity of the assays and methods they used.

“As SARS-CoV-2 neutralization assays are, to this point, still highly variable and in the process of being further developed, optimized and validated, study measurements should not be considered a strong predictor of clinical outcomes, especially in the absence of results from a positive control that has demonstrated disease enhancement,” Moderna said.

“Clearly, both Moderna and FDA knew about disease enhancement and were aware of numerous examples of this dangerous phenomenon, including Moderna’s own Zika vaccine product of the same type,” Latypova said. “Yet, the FDA did not question Moderna’s scientifically dishonest ‘studies’ that dismissed this extremely significant risk without a proper study design.”

Finding 6: FDA and Moderna lied about reproductive toxicology studies in public disclosures and product labeling.

Although the FDA recommends Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine for pregnant and lactating women, Moderna conducted only one reproductive toxicology study in pregnant and lactating rats using a human dose of 100 mcg of mRNA-1273.

Although the full study was excluded, a narrative summary of Moderna’s findings state, “high IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 S-2P were also observed in GD 21 F1 fetuses and LD 21 F1 pups, indicating strong transfer of antibodies from dam to fetus and from dam to pup.”

Latypova said safety assessments in the study are very limited, but the following findings are described by Moderna:

“The mothers lost fur after vaccine administration, and it persisted for several days. No information on when it was fully resolved since the study was terminated before this could be assessed.”

In the rat pups, the following skeletal malformations were observed:

“In the F1 generation [rat pups], there were no mRNA-1273-related effects or changes in the following parameters: mortality, body weight, clinical observations, macroscopic observations, gross pathology, external or visceral malformations or variations, skeletal malformations, and mean number of ossification sites per fetus per litter.

“mRNA-1273-related variations in skeletal examination included statistically significant increases in the number of F1 rats with 1 or more wavy ribs and 1 or more rib nodules.

“Wavy ribs appeared in 6 fetuses and 4 litters with a fetal prevalence of 4.03% and a litter prevalence of 18.2%. Rib nodules appeared in 5 of those 6 fetuses.”

Moderna related the skeletal malformations to days when toxicity was observed in the mothers but waived away the finding as “unrelated to the vaccine,” Latypova said.

The FDA then “lied on Moderna’s behalf” in its Basis for Regulatory Action Summary document (p.14) stating “no skeletal malformations” occurred in the non-clinical study in rat pups despite the opposite reported by Moderna.

“No vaccine-related fetal malformations or variations and no adverse effect on postnatal development were observed in the study. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) responses to the pre-fusion stabilized spike protein antigen following immunization were observed in maternal samples and F1 generation rats indicating transfer of antibodies from mother to fetus and from mother to nursing pups.”

“In summary, the vaccine-derived antibodies transfer from mother to child,” Latypova said. “It was never assessed by Moderna whether the LNPs, mRNA and spike proteins transfer as well, but it is reasonable to assume that they do due to the mechanism of action of these products.”

Latypova said studies should have been done to assess the risks to the child by vaccinating pregnant or lactating women before recommending these groups receive a COVID-19 vaccine.

“We should ask the question why are they concealing the critical safety-related information from public, and making the product look better than the manufacturer has admitted,” Latypova said.

“The FDA did not have any objective scientific evidence excluding the skeletal malformations being related to the vaccine,” she added. “Thus, the information should have been disclosed fully in the label of this experimental and poorly tested product — not hidden from the public for over a year and then disclosed only under a court order.”

Latypova said FDA reviewers should have “easily seen through the blatant fraud, omissions, use of inadequate study designs and general lack of scientific rigor.”

The fact that more than half of the document package contains non-GLP studies for irrelevant, unapproved and previously failed chemical entities alone should have been sufficient reason to not approve this product, she added.

It would appear the FDA based its decision that the product is safe to administer to thousands of otherwise healthy humans on two studies in rats, Latypova said. The rest of the 700-page package was deemed to consist of “other supportive studies.”

The FDA noted studies were conducted in “five vaccines formulated in SM-102 lipid particles containing mRNAs encoding various viral glycoprotein antigens” but “failed to mention that these were five unapproved and previously failed products,” she said.

The regulators then concluded that using novel unapproved mRNAs in support of another unapproved novel mRNA was acceptable.

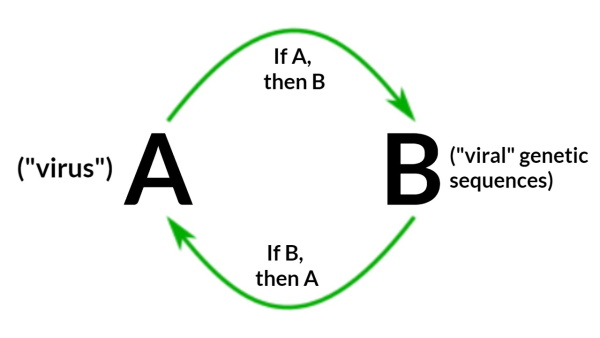

“The circular logic is astonishing,” Latypova said. Regulators allowed and personally promoted the use of failed experiments in support of a different and new experiment directly on the unsuspecting public.

Latypova called for the FDA, pharmaceutical manufacturers and “all other perpetrators of this fraud to be urgently stopped and investigated.”

©July 2022 Children’s Health Defense, Inc. This work is reproduced and distributed with the permission of Children’s Health Defense, Inc. Want to learn more from Children’s Health Defense? Sign up for free news and updates from Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and the Children’s Health Defense. Your donation will help to support us in our efforts.

Connect with The Defender

Why 5G matters

Why 5G matters

BREAKING: A federal court granted our request for discovery & documents from top ranking Biden officials & social media companies to get to the bottom of their collusion to suppress & censor free speech.

BREAKING: A federal court granted our request for discovery & documents from top ranking Biden officials & social media companies to get to the bottom of their collusion to suppress & censor free speech. (@KatieDaviscourt)

(@KatieDaviscourt)

(@approject)

(@approject)