Transcript created by Truth Comes to Light

October 7, 2020

This is an unofficial transcript of Dr. Reiner Fuellmich’s “Crimes Against Humanity” video, published on Octber 3, 2020.

See Dr. Reiner Fuellmich’s powerful, inspiring video here: https://truthcomestolight.com/2020/10/04/dr-reiner-fuellmich-on-the-corona-fraud-scandal-international-network-of-lawyers-will-argue-the-biggest-tort-case-in-world-history/

Hello. I am Reiner Fuellmich and I have been admitted to the Bar in Germany and in California for 26 years.

I have been practicing law, primarily as a trial lawyer, against fraudulent corporations such as

Deutsche Bank, formerly one of the world’s largest and most respected banks, today one of the most toxic criminal organizations in the world; VW, one of the world’s largest and most respected car manufacturers, today notorious for its giant diesel fraud; and Kuehne+Nagel, the world’s largest shipping company. We’re suing them in a multi-million-dollar bribery case.

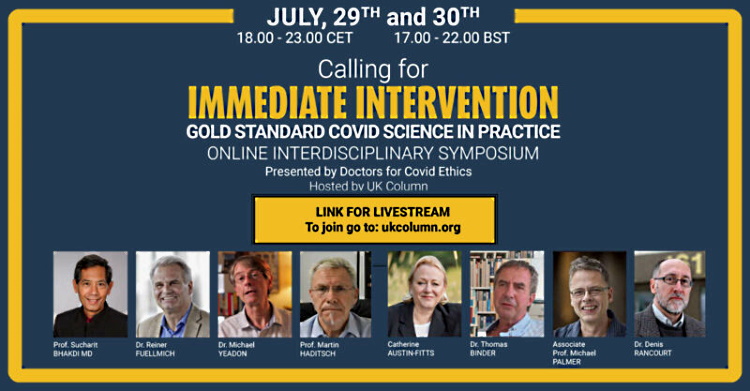

I’m also one of four members of the German Corona Investigative Committee. Since July 10th 2020, this Committee has been listening to a large number of international scientists’ and experts’ testimony to find answers to questions about the corona crisis, which more and more people worldwide are asking.

All the above-mentioned cases of corruption and fraud committed by the German corporations pale in comparison in view of the extent of the damage that the corona crisis has caused and continues to cause.

This corona crisis, according to all we know today, must be renamed a “Corona Scandal” and those responsible for it must be criminally prosecuted and sued for civil damages.

On a political level, everything must be done to make sure that no one will ever again be in a position of such power as to be able to defraud humanity or to attempt to manipulate us with their corrupt agendas.

And for this reason, I will now explain to you how and where an international network of lawyers will argue this biggest tort case ever, “The Corona Fraud Scandal”, which has meanwhile unfolded into probably the greatest crime against humanity ever committed.

“Crimes against humanity” were first defined in connection with the Nuremberg trials — after World War II, that is — when they dealt with the main war criminals of the Third Reich.

“Crimes against humanity” are today regulated in Section 7 of the International Criminal Code.

The three major questions to be answered in the context of a judicial approach to the Corona Scandal are:

1) Is there a corona pandemic or is there only a PCR-test pandemic? Specifically, does a positive PCR-test result mean that the person tested is infected with Covid-19, or does it mean absolutely nothing in connection with the Covid-19 infection?

2) Do the so-called anti-corona measures, such as the lockdown, mandatory face masks, social distancing, and quarantine regulations, serve to protect the world’s population from corona? Or do these measures serve only to make people panic so that they believe, without asking any questions, that their lives are in danger — so that, in the end, the pharmaceutical and tech industries can generate huge profits from the sale of PCR tests, antigen and antibody tests and vaccines, as well as the harvesting of our genetic fingerprints?

3) Is it true that the German government was massively lobbied, more so than any other country, by the chief protagonists of this so-called corona pandemic (Mr. Drosten, virologist at Charité Hospital in Berlin; Mr. Wieler, veterinarian and head of the German equivalent of the CDC, the RKI; and Mr. Tedros, head of the World Health Organization or WHO) because Germany is known as a particularly disciplined country and was therefore to become a role model for the rest of the world for its strict and, of course, successful adherence to the corona measures?

Answers to these three questions are urgently needed because the allegedly new and highly dangerous coronavirus has not caused any excess mortality anywhere in the world, and certainly not here in Germany.

But the anti-corona measures, whose only basis are the PCR-test results, which are in turn all based on the German Drosten test, have, in the meantime, caused the loss of innumerable human lives and have destroyed the economic existence of countless companies and individuals worldwide.

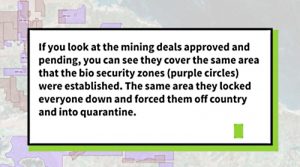

In Australia, for example, people are thrown into prison if they do not wear a mask or do not wear it properly, as deemed by the authorities.

In the Philippines, people who do not wear a mask or do not wear it properly, in this sense, are getting shot in the head.

Let me first give you a summary of the facts as they present themselves today.

The most important thing in a lawsuit is to establish the facts — that is, to find out what actually happened. That is because the application of the law always depends on the facts at issue. If I want to prosecute someone for fraud, I cannot do that by presenting the facts of a car accident. So what happened here regarding the alleged corona pandemic?

The facts laid out below are, to a large extent, the result of the work of the Corona Investigative Committee. This Committee was founded on July 10th by four lawyers in order to determine, through hearing expert testimony of international scientists and other experts.

1) How dangerous is the virus really?

2) What is the significance of a positive PCR test?

3) What collateral damage has been caused by the corona measures, both with respect to the world population’s health, and with respect to the world’s economy?

Let me start with a little bit of background information.

What happened in May 2019 and then in early 2020? And what happened 12 years earlier with the swine flu, which many of you may have forgotten about?

In May 2019, the stronger of the two parties which govern Germany in a grand coalition, the CDU, held a Congress on Global Health, apparently at the instigation of important players from the pharmaceutical industry and the tech industry.

At this Congress, the usual suspects, you might say, gave their speeches. Angela Merkel was there, and the German Secretary of Health, Jens Spahn.

But, some other people, whom one would not necessarily expect to be present at such a gathering, were also there: Professor Drosten, virologist from the Charité Hospital in Berlin; Professor Wieler, veterinarian and head of the RKI, the German equivalent of the CDC; as well as Mr. Tedros, philosopher and head of the World Health Organization (WHO). They all gave speeches there.

Also present and giving speeches were the chief lobbyists of the world’s two largest health funds, namely the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust.

Less than a year later, these very people called the shots in the proclamation of the worldwide corona pandemic, made sure that mass PCR tests were used to prove mass infections with Covid-19 all over the world, and are now pushing for vaccines to be invented and sold worldwide.

These infections, or rather the positive test results that the PCR tests delivered, in turn became the justification for worldwide lockdowns, social distancing and mandatory face masks.

It is important to note at this point that the definition of a pandemic was changed 12 years earlier. Until then, a pandemic was considered to be a disease that spread worldwide and which led to many serious illnesses and deaths. Suddenly, and for reasons never explained, it was supposed to be a worldwide disease only. Many serious illnesses and many deaths were not required any more to announce a pandemic.

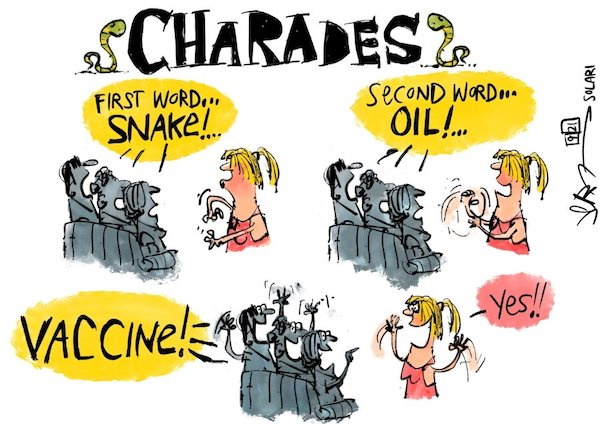

Due to this change, the WHO, which is closely intertwined with the global pharmaceutical industry, was able to declare the swine flu pandemic in 2009, with the result that vaccines were produced and sold worldwide on the basis of contracts that have been kept secret until today.

These vaccines proved to be completely unnecessary because the swine flu eventually turned out to be a mild flu, and never became the horrific plague that the pharmaceutical industry and its affiliated universities kept announcing it would turn into — with millions of deaths certain to happen if people didn’t get vaccinated.

These vaccines also led to serious health problems. About 700 children in Europe fell incurably ill with narcolepsy and are now forever severely disabled.

The vaccines bought with millions of taxpayers’ money had to be destroyed with even more taxpayers’ money. Already then, during the swine flu, the German virologist Drosten was one of those who stirred up panic in the population, repeating over and over again that the swine flu would claim many hundreds of thousands, even millions of deaths all over the world.

In the end, it was mainly thanks to Dr. Wolfgang Wodarg and his efforts as a member of the German Bundestag, and also a member of the Council of Europe, that this hoax was brought to an end before it would lead to even more serious consequences.

Fast forward to March of 2020. When the German Bundestag announced an Epidemic Situation of National Importance — which is the German equivalent of a pandemic — in March of 2020 and, based on this, the lockdown, with the suspension of all essential constitutional rights for an unforeseeable time, there was only one single opinion on which the federal government in Germany based its decision.

In an outrageous violation of the universally accepted principle “audiatur et altera pars”, which means that one must also hear the other side, the only person they listened to was Mr. Drosten.

That is the very person whose horrific, panic-inducing prognoses had proved to be catastrophically false 12 years earlier. We know this because a whistleblower named David Sieber, a member of the Green Party, told us about it. He did so first on August 29th 2020 in Berlin, in the context of an event at which Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. also took part, and at which both men gave speeches. And he did so afterwards in one of the sessions of our Corona Committee.

The reason he did this is that he had become increasingly sceptical about the official narrative propagated by politicians and the mainstream media. He had, therefore, undertaken an effort to find out about other scientists’ opinions and had found them on the internet.

There, he realized that there were a number of highly-renowned scientists who held a completely different opinion, which contradicted the horrific prognoses of Mr. Drosten.

They assumed, and still do assume, that there was no disease that went beyond the gravity of the seasonal flu — that the population had already acquired cross- or T-cell immunity against this allegedly new virus, and that there was, therefore, no reason for any special measures. And certainly not for vaccinations.

These scientists include: Professor John Ioannidis of Stanford University in California, a specialist in statistics and epidemiology, as well as public health, and at the same time the most quoted scientist in the world; Professor Michael Levitt, Nobel prize-winner for chemistry and also a biophysicist at Stanford University; the German professors Karin Mölling, Sucharit Bhakdi, Knut Wittkowski, as well as Stefan Homburg; and now many, many more scientists and doctors worldwide, including Dr. Mike Yeadon.

Dr. Mike Yeadon is the former vice president and Scientific Director of Pfizer, one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. I will talk some more about him a little later.

At the end of March / beginning of April of 2020, Mr. Sieber turned to the leadership of his Green Party with the knowledge he had accumulated, and suggested that they present these other scientific opinions to the public and explain that, contrary to Mr. Drosten’s doomsday prophecies, there was no reason for the public to panic.

Incidentally, Lord Sumption, who served as a judge at the British Supreme Court from 2012 to 2018, had done the very same thing at the very same time and had come to the very same conclusion: that there was no factual basis for panic and no legal basis for the corona measures.

Likewise, the former president of the German federal constitutional court expressed, albeit more cautiously, serious doubts that the corona measures were constitutional. But instead of taking note of these other opinions and discussing them with David Sieber, the Green Party leadership declared that Mr. Drosten’s panic messages were good enough for the Green Party. Remember, they’re not a member of the ruling coalition; they’re the opposition. Still, that was enough for them, just as it had been good enough for the federal government as a basis for its lockdown decision, they said.

They subsequently — the Green Party leadership — called David Sieber a conspiracy theorist without ever having considered the content of his information, and then stripped him of his mandates.

Now let’s take a look at the current actual situation regarding the virus’s danger, the complete uselessness of PCR tests for the detection of infections, and the lockdowns based on non-existent infections.

In the meantime, we know that the health care systems were never in danger of becoming overwhelmed by Covid-19. On the contrary, many hospitals remain empty to this day and some are now facing bankruptcy.

The hospital ship Comfort, which anchored in New York at the time, and could have accommodated a thousand patients, never accommodated more than some 20 patients.

Nowhere was there any excess mortality. Studies carried out by Professor Ioannidis and others have shown that the mortality of corona is equivalent to that of the seasonal flu.

Even the pictures from Bergamo and New York, that were used to demonstrate to the world that panic was in order, proved to be deliberately misleading.

Then, the so-called “panic paper” was leaked, which was written by the German Department of the Interior. Its classified content shows, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that, in fact, the population was deliberately driven to panic by politicians and mainstream media.

The accompanying irresponsible statements of the head of the RKI (remember the CDC), Mr. Wieler, who repeatedly and excitedly announced that the corona measures must be followed unconditionally by the population without them asking any question, shows that he followed the script verbatim. In his public statements, he kept announcing that the situation was very grave and threatening, although the figures compiled by his own institute proved the exact opposite.

Among other things, the “panic paper” calls for children to be made to feel responsible, and I quote: “for the painful, tortured death of their parents and grandparents if they do not follow the corona rules”, that is, if they do not wash their hands constantly and don’t stay away from their grandparents.

A word of clarification: In Bergamo, the vast majority of deaths, 94% to be exact, turned out to be the result not of Covid-19, but rather the consequence of the government deciding to transfer sick patients — sick with probably the cold or seasonal flu — from hospitals to nursing homes in order to make room at the hospitals for all the Covid patients, who ultimately never arrived.

There, at the nursing homes, they then infected old people with a severely weakened immune system, usually as a result of pre-existing medical conditions.

In addition, a flu vaccination, which had previously been administered, had further weakened the immune systems of the people in the nursing homes.

In New York, only some, but by far not all, hospitals were overwhelmed.

Many people — most of whom were, again, elderly and had serious pre-existing medical conditions and most of whom, had it not been for the panic mongering, would have just stayed at home to recover — raced to the hospitals.

There, many of them fell victim to healthcare-associated infections (or nosocomial infections) on the one hand, and incidents of malpractice on the other hand — for example, by being put on a respirator rather than receiving oxygen through an oxygen mask.

Again, to clarify: Covid-19, this is the current state of affairs, is a dangerous disease. Just like the seasonal flu is a dangerous disease. And of course, Covid-19, just like the seasonal flu, may sometimes take take a severe clinical course and will sometimes kill patients.

However, as autopsies have shown — which were carried out in Germany, in particular by the forensic scientist Professor Klaus Püschel, in Hamburg — the fatalities he examined had almost all been caused by serious pre-existing conditions and almost all of the people who had died, had died at a very old age just like in Italy. Meaning they had lived beyond their average life expectancy.

In this context, the following should also be mentioned: the German RKI – that is, again, the equivalent of the CDC – had initially, strangely enough, recommended that no autopsies be performed.

And there are numerous credible reports that doctors and hospitals worldwide had been paid money for declaring a deceased person a victim of Covid-19 rather than writing down the true cause of death on the death certificate — for example, a heart attack or a gunshot wound.

Without the autopsies, we would never know that the overwhelming majority of the alleged Covid-19 victims had died of completely different diseases, but not of Covid-19. The assertion that the lockdown was necessary because there were so many different infections with SARS-CoV-2, and because the healthcare systems would be overwhelmed is wrong for three reasons, as we have learned from the hearings we conducted with the Corona Committee, and from other data that has become available in the meantime.

a) The lockdown was imposed when the virus was already retreating. By the time the lockdown was imposed, the alleged infection rates were already dropping again.

b) There’s already protection from the virus because of cross- or T-cell immunity. Apart from the above mentioned lockdown being imposed when the infection rates were already dropping, there is also cross- or T-cell immunity in the general population against the corona viruses contained in every flu or influenza wave.

This is true, even if this time around, a slightly different strain of the coronavirus was at work. And that is because the body’s own immune system remembers every virus it has ever battled in the past, and from this experience, it also recognizes a supposedly new, but still similar, strain of the virus from the corona family. Incidentally, that’s how the PCR test for the detection of an infection was invented by now infamous Professor Drosten.

At the beginning of January of 2020, based on this very basic knowledge, Mr. Drosten developed his PCR test, which supposedly detects an infection with SARS-CoV-2, without ever having seen the real Wuhan virus from China.

Only having learned from social media reports that there was something going on in Wuhan, he started tinkering on his computer with what would become his corona PCR test.

For this, he used an old SARS virus, hoping it would be sufficiently similar to the allegedly new strain of the coronavirus found in Wuhan. Then, he sent the result of his computer tinkering to China to determine whether the victims of the alleged new coronavirus tested positive. They did.

And that was enough for the World Health Organization to sound the pandemic alarm and to recommend the worldwide use of the Drosten PCR test for the detection of infections with the virus now called SARS-CoV-2.

Drosten’s opinion and advice was — this must be emphasized once again — the only source for the German government when it announced the lockdown as well as the rules for social distancing and the mandatory wearing of masks.

And, this must also be emphasized once again — Germany, apparently, became the centre of, especially, massive lobbying by the pharmaceutical and tech industry because the world was referenced to the allegedly disciplined Germans, should do as the Germans do, in order to survive the pandemic.

c) And this is the most important part of our fact-finding. The PCR test is being used on the basis of false statements, not based on scientific facts with respect to infections. In the meantime, we have learned that these PCR tests, contrary to the assertions of Messrs. Drosten, Wieler and the WHO, do not give any indication of an infection with any virus let alone an infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Not only are PCR tests expressly not approved for diagnostic purposes — as is correctly noted on leaflets coming with these tests, and as the inventor of the PCR test, Kary Mullis, has repeatedly emphasized. Instead, they’re simply incapable of diagnosing any disease.

That is, contrary to the assertions of Drosten, Wieler and the WHO, which they have been making since the proclamation of the pandemic, a positive PCR test result does not mean that an infection is present.

If someone tests positive, it does not mean that they’re infected with anything let alone with the contagious SARS-CoV-2 virus. Even the United States CDC, even this institution, agrees with this and I quote directly from page 38 of one of its publications on the coronavirus and the PCR tests, dated July 13 2020:

First bullet point says: “Detection of viral RNA may not indicate the presence of infectious virus or that 2019 nCoV is the causative agent for clinical symptoms.”

Second bullet point says: “The performance of this test has not been established for monitoring treatment of two threat 2019 nCoV infection.”

Third bullet point says: “This test cannot rule out diseases caused by other bacterial or viral pathogens.”

It is still not clear whether there has ever been a scientifically-correct isolation of the Wuhan virus, so that nobody knows exactly what we’re looking for when we test — especially, since this virus, just like the flu viruses, mutates quickly.

The PCR swabs take one or two sequences of a molecule that are invisible to the human eye, and therefore need to be amplified in many cycles to make it visible. Everything over 35 cycles is, as reported by the New York Times and others, considered completely unreliable and scientifically unjustifiable.

However, the Drosten test, as well as the WHO-recommended tests that followed his example, are set to 45 cycles. Can that be because of the desire to produce as many positive results as possible and, thereby, provide the basis for the false assumption that a large number of infections have been detected?

The test cannot distinguish inactive and reproductive matter.

That means that a positive result may happen because the test detects, for example, a piece of debris — a fragment of a molecule, which may signal nothing else more than the immune system of the person tested won a battle with a common cold in the past.

Even Drosten himself declared in an interview with a German business magazine in 2014 — at that time concerning the alleged detection of an infection with the MERS virus, allegedly with the help of the PCR test — that these PCR tests are so highly sensitive that even very healthy and non-infectious people may test positive.

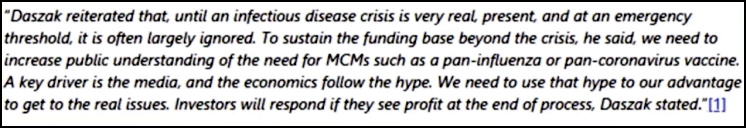

At that time, he also became very much aware of the powerful role of a panic and fear-mongering media, as you’ll see at the end of the following quote.

He said then, in this interview: “If, for example, such a pathogen scurries over the nasal mucosa of a nurse for a day or so without her getting sick or noticing anything, then she’s suddenly a MERS case.

This could also explain the explosion of case numbers in Saudi Arabia. In addition, the media there have made this into an incredible sensation.”

Has he forgotten this? Or is he deliberately concealing this in the corona context because corona is a very lucrative business opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry as a whole, and for Mr. Alford Lund, his co-author in many studies, and also a PCR test producer?

In short, this test cannot detect any infection, contrary to all false claims stating that it can.

An infection, a so-called hot infection, requires that the virus, or rather a fragment of a molecule which may be a virus, is not just found somewhere — for example, in the throat of a person without causing any damage (that would be a cold infection).

Rather, a hot infection requires that the virus penetrates into the cells, replicates there and causes symptoms such as headaches or a sore throat. Only then is a person really infected in the sense of a hot infection, because only then is a person contagious — that is able to infect others. Until then, it is completely harmless for both the host and all other people that the host comes into contact with.

Once again, this means that positive test results, contrary to all other claims by Drosten, Wieler or the WHO mean nothing with respect to infections, as even the CDC knows, as quoted above.

Meanwhile, a number of highly-respected scientists worldwide assume that there has never been a corona pandemic, but only a PCR test pandemic.

This is the conclusion reached by many German scientists such as professors Bhakdi, Reiss, Mölling, Hockerts, Walach and many others — including the above mentioned Professor John Ioannidis and the Nobel laureate, Professor Michael Levitt, from Stanford University.

The most recent such opinion is that of the aforementioned Dr. Mike Yeadon, a former vice president and chief science officer at Pfizer, who held this position for 16 years. He and his co-authors, all well-known scientists, published a scientific paper in September of 2020 and he wrote a corresponding magazine article on September 20th 2020.

Among other things, he and they state, and I quote:

“We’re basing our government policy, our economic policy and the policy of restricting fundamental rights presumably on completely wrong data and assumptions about the coronavirus. If it weren’t for the test results that are constantly reported in the media, the pandemic would be over, because nothing really happened.

“Of course, there are some serious individual cases of illness but there are also some in every flu epidemic. There was a real wave of disease in March and April but since then everything has gone back to normal. Only the positive results rise and sink wildly again and again, depending on how many tests are carried out. But the real cases of illnesses are over.

“There can be no talk of a second wave.

“The allegedly new strain of the coronavirus is”, Dr Yeadon continues, “only new in that it is a new type of the long known coronavirus.

“There are at least four coronaviruses that are endemic and cause some of the common colds we experience, especially in winter. They all have a striking sequence similarity to the coronavirus, and because the human immune system recognises the similarity to the virus that has now allegedly been newly discovered, a t-cell immunity has long existed in this respect.

“Thirty percent of the population had this before the allegedly-new virus even appeared. Therefore, it is sufficient for the so-called herd immunity that 15 to 25 percent of the population are infected with the allegedly-new coronavirus to stop the further spread of the virus. And this has long been the case.”

Regarding the all-important PCR tests, Yeadon writes in a piece called: ‘Lies, Damned Lies and Health Statistics – the Deadly Danger of False Positives’ dated September 20th 2020, and I quote: “The likelihood of an apparently positive case being a false positive is between 89 to 94 percent or near certainty.”

Dr. Yeadon, in agreement with the professors of immunology Kamera from Germany, Kappel from the Netherlands, and Cahill from Ireland, as well as the microbiologist Dr. Arve from Austria, all of whom testified before the German Corona Committee, explicitly points out that a positive test does not mean that an intact virus has been found.

The authors explain that what the PCR test actually measures is, and I quote: “…simply the presence of partial RNA sequences present in the intact virus, which could be a piece of dead virus, which cannot make the subject sick, and cannot be transmitted, and cannot make anyone else sick.”

Because of the complete unsuitability of the test for the detection of infectious diseases — tested positive in goats, sheep, papayas and even chicken wings — Oxford Professor Carl Heneghan, Director of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, writes that the Covid virus would never disappear if this test practice were to be continued, but would always be falsely detected in much of what is tested.

Lockdowns, as Yeadon and his colleagues found out, do not work.

Sweden, with its laissez-faire approach, and Great Britain, with its strict lockdown, for example, have completely comparable disease and mortality statistics. The same was found by US scientists concerning the different US states. It makes no difference to the incidence of disease whether a state implements a lockdown or not.

With regard to the now infamous Imperial College of London’s Professor Neil Ferguson and his completely false computer models warning of millions of deaths, he says that, and I quote: “No serious scientist gives any validity to Ferguson’s model.” He points out with thinly veiled contempt — again, I quote:

“It’s important that you know, most scientists don’t accept that it (that is, Ferguson’s model) was even faintly right. But the government is still wedded to the model.”

Ferguson predicted 40 thousand corona deaths in Sweden by May and a hundred thousand by June, but it remained at 5,800 which, according to the Swedish authorities, is equivalent to a mild flu.

If the PCR tests had not been used as a diagnostic tool for corona infections, there would not be a pandemic and there would be no lockdowns. But everything would have been perceived as just a medium or light wave of influenza, these scientists conclude.

Dr. Yeadon in his piece “Lies, Damned Lies and Health Statistics: The Deadly Danger of False Positives“, writes: “This test is fatally flawed and must immediately be withdrawn and never used again in this setting, unless shown to be fixed.” And, towards the end of that article, “I have explained how a hopelessly performing diagnostic test has been, and continues to be used, not for diagnosis of disease, but it seems solely to create fear”.

Now let’s take a look at the current actual situation regarding the severe damage caused by the lockdowns and other measures.

Another detailed paper, written by a German official in the Department of the Interior, who is responsible for risk assessment and the protection of the population against risks, was leaked recently. It is now called the “false alarm” paper.

This paper comes to the conclusion that there was, and is, no sufficient evidence for serious health risks for the population as claimed by Drosten, Wieler and the WHO. But, the author says, there’s very much evidence of the corona measures causing gigantic health and economic damage to the population, which he then describes in detail in this paper. This, he concludes, will lead to very high claims for damages, which the government will be held responsible for. This has now become reality, but the paper’s author was suspended.

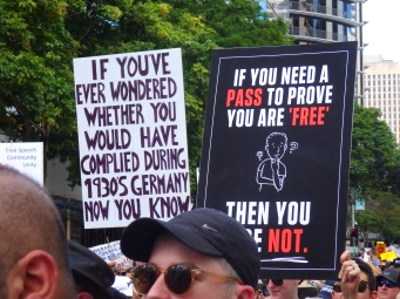

More and more scientists, but also lawyers, recognize that, as a result of the deliberate panic-mongering, and the corona measures enabled by this panic, democracy is in great danger of being replaced by fascist totalitarian models.

As I already mentioned above, in Australia, people who do not wear the masks — which more and more studies show, are hazardous to health — or, who allegedly do not wear them correctly, are arrested, handcuffed and thrown into jail.

In the Philippines, they run the risk of getting shot.

But even in Germany, and in other previously civilized countries, children are taken away from their parents if they do not comply with quarantine regulations, distance regulations, and mask-wearing regulations.

According to psychologists and psychotherapists who testified before the Corona Committee, children are traumatized en masse, with the worst psychological consequences yet to be expected in the medium and long-term.

In Germany alone, 500,000 to 800,000 bankruptcies are expected in the fall to strike small and medium-sized businesses, which form the backbone of the economy. This will result in incalculable tax losses and incalculably high and long-term social security money transfers for, among other things, unemployment benefits.

Since, in the meantime, pretty much everybody is beginning to understand the full devastating impact of the completely unfounded corona measures, I will refrain from detailing this any further.

Let me now give you a summary of the legal consequences.

The most difficult part of a lawyer’s work is always to establish the true facts, not the application of the legal rules to these facts.

Unfortunately, a German lawyer does not learn this at law school. But his Anglo-American counterparts do get the necessary training for this at their law schools. And probably for this reason, but also because of the much more pronounced independence of the Anglo-American judiciary, the Anglo-American law of evidence is much more effective in practice than the German one.

A court of law can only decide a legal dispute correctly if it has previously determined the facts correctly, which is not possible without looking at all the evidence. And that’s why the law of evidence is so important.

On the basis of the facts summarized above, in particular those established with the help of the work of the German Corona Committee, the legal evaluation is actually simple. It is simple for all civilized legal systems, regardless of whether these legal systems are based on civil law, which follows the Roman law more closely, or whether they are based on Anglo-American common law, which is only loosely connected to Roman law.

Let’s first take a look at the unconstitutionality of the measures.

A number of German law professors, including professors Kingreen, Morswig, Jungbluth and Vosgerau have stated, either in written expert opinions or in interviews — in line with the serious doubts expressed by the former president of the federal constitutional court with respect to the constitutionality of the corona measures — that these measures (the corona measures) are without a sufficient factual basis, and also without a sufficient legal basis, and are, therefore, unconstitutional and must be repealed immediately.

Very recently a judge, Thorsten Schleif is his name, declared publicly that the German judiciary, just like the general public, has been so panic-stricken that it was no longer able to administer justice properly. He says that the courts of law, and I quote: “…have all too quickly waved through coercive measures which, for millions of people all over Germany, represent massive suspensions of their constitutional rights.”

He points out that German citizens, again, I quote: “…are currently experiencing the most serious encroachment on their constitutional rights since the founding of the federal republic of Germany in 1949.”

“In order to contain the corona pandemic, federal and state governments have intervened,” he says, “massively, and in part threatening the very existence of the country as it is guaranteed by the constitutional rights of the people.”

What about fraud, intentional infliction of damage and crimes against humanity?

Based on the rules of criminal law, asserting false facts concerning the PCR tests or intentional misrepresentation, as it was committed by Messrs. Drosten, Wieler, as well as the WHO, can only be assessed as fraud.

Based on the rules of civil tort law, this translates into intentional infliction of damage.

The German professor of civil law, Martin Schwab, supports this finding in public interviews. In a comprehensive legal opinion of around 180 pages, he has familiarized himself with the subject matter like no other legal scholar has done thus far and, in particular, has provided a detailed account of the complete failure of the mainstream media to report on the true facts of this so-called pandemic.

Messrs. Drosten, Wieler and Tedros of the WHO all knew, based on their own expertise or the expertise of their institutions, that the PCR tests cannot provide any information about infections, but asserted over and over again to the general public that they can, with their counterparts all over the world repeating this.

And they all knew and accepted that, on the basis of their recommendations, the governments of the world would decide on lockdowns, the rules for social distancing, and mandatory wearing of masks, the latter representing a very serious health hazard, as more and more independent studies and expert statements show.

Under the rules of civil tort law, all those who have been harmed by these PCR-test-induced lockdowns are entitled to receive full compensation for their losses. In particular, there is a duty to compensate — that is, a duty to pay damages for the loss of profits suffered by companies and self-employed employed persons as a result of the lockdown and other measures.

In the meantime, however, the anti-corona measures have caused, and continue to cause, such devastating damage to the world population’s health and economy that the crimes committed by Messrs. Drosten, Wieler and the WHO must be legally qualified as actual crimes against humanity, as defined in Section 7 of the International Criminal Code.

How can we do something? What can we do?

Well, the class action is the best route to compensatory damages and to political consequences. The so-called class action lawsuit is based on English law and exists today in the USA and in Canada. It enables a court of law to allow a complaint for damages to be tried as a class action lawsuit at the request of a plaintiff if:

1) As a result of a damage-inducing event.

2) A large number of people suffer the same type of damage.

Phrased differently, a judge can allow a class-action lawsuit to go forward if common questions of law and fact make up the vital component of the lawsuit.

Here, the common questions of law and fact revolve around the worldwide PCR-test-based lockdowns and its consequences.

Just like the VW diesel passenger cars were functioning products, but they were defective due to a so-called defeat device (because they didn’t comply with the emissions standards), so too the PCR tests, which are perfectly good products in other settings, are defective products when it comes to the diagnosis of infections.

Now, if an American or Canadian company or an American or Canadian individual decides to sue these persons in the United States or Canada for damages, then the court called upon to resolve this dispute may, upon request, allow this complaint to be tried as a class action lawsuit.

If this happens, all affected parties worldwide will be informed about this through publications in the mainstream media and will thus have the opportunity to join this class action within a certain period of time, to be determined by the court. It should be emphasized that nobody must join the class action, but every injured party can join the class.

The advantage of the class action is that only one trial is needed, namely to try the complaint of a representative plaintiff who is affected in a manner typical of everyone else in the class. This is, firstly, cheaper, and secondly, faster than hundreds of thousands or more individual lawsuits. And thirdly, it imposes less of a burden on the courts. Fourthly, as a rule it allows a much more precise examination of the accusations than would be possible in the context of hundreds of thousands, or more likely in this corona setting, even millions of individual lawsuits.

In particular, the well-established and proven Anglo-American law of evidence, with its pre-trial discovery, is applicable. This requires that all evidence relevant for the determination of the lawsuit is put on the table. In contrast to the typical situation in German lawsuits with structural imbalance — that is, lawsuits involving on the one hand a consumer, and on the other hand a powerful corporation — the withholding or even destruction of evidence is not without consequence. Rather the party withholding or even destroying evidence loses the case under these evidence rules.

Here in Germany, a group of tort lawyers have banded together to help their clients with recovery of damages. They have provided all relevant information and forms for German plaintiffs to both estimate how much damage they have suffered and join the group or class of plaintiffs who will later join the class action when it goes forward either in Canada or the US. Initially, this group of lawyers had considered to also collect and manage the claims for damages of other, non-German plaintiffs, but this proved to be unmanageable.

However, through an international lawyers’ network, which is growing larger by the day, the German group of attorneys provides to all of their colleagues in all other countries, free of charge, all relevant information, including expert opinions and testimonies of experts showing that the PCR tests cannot detect infections. And they also provide them with all relevant information as to how they can prepare and bundle the claims for damages of their clients so that, they too, can assert their clients’ claims for damages, either in their home country’s courts of law, or within the framework of the class action, as explained above.

These scandalous corona facts, gathered mostly by the Corona Committee and summarized above, are the very same facts that will soon be proven to be true either in one court of law, or in many courts of law all over the world.

These are the facts that will pull the masks off the faces of all those responsible for these crimes.

To the politicians who believe those corrupt people, these facts are hereby offered as a lifeline that can help you readjust your course of action, and start the long overdue public scientific discussion, and not go down with those charlatans and criminals.

Thank you.

Sharon James — along with her husband, children & visiting grandchildren — has lived and worked for nearly 35 years on a century farm in Iowa.

Sharon James — along with her husband, children & visiting grandchildren — has lived and worked for nearly 35 years on a century farm in Iowa.